The Chaos of Driving in Lebanon Tells a Story of a Country Unraveled

By Nada Bakri

The New York Times

A video clip that circulated this year on social media in Lebanon shows a man in a car, playing two roles: a driving instructor and a student. It’s a deadpan sketch aimed at Lebanon’s traffic chaos — or, read another way, a satirical portrait of a people shaped by collapse.

“How do you drive on the highway?” the instructor asks. “Slowly,” the student answers. “Bravo,” the instructor says and checks a box.

“If someone is driving behind you?” “I slam on the brakes.” The instructor nods approvingly.

“If someone pulls up next to you?” “I swerve into them.” “Very good.”

“Someone tries to merge into your lane?” “I block them.” “Love it,” the instructor answers.

“Shall we begin?” the student finally asks. “We are done,” the instructor replies and hands him the key. “Congratulations.”

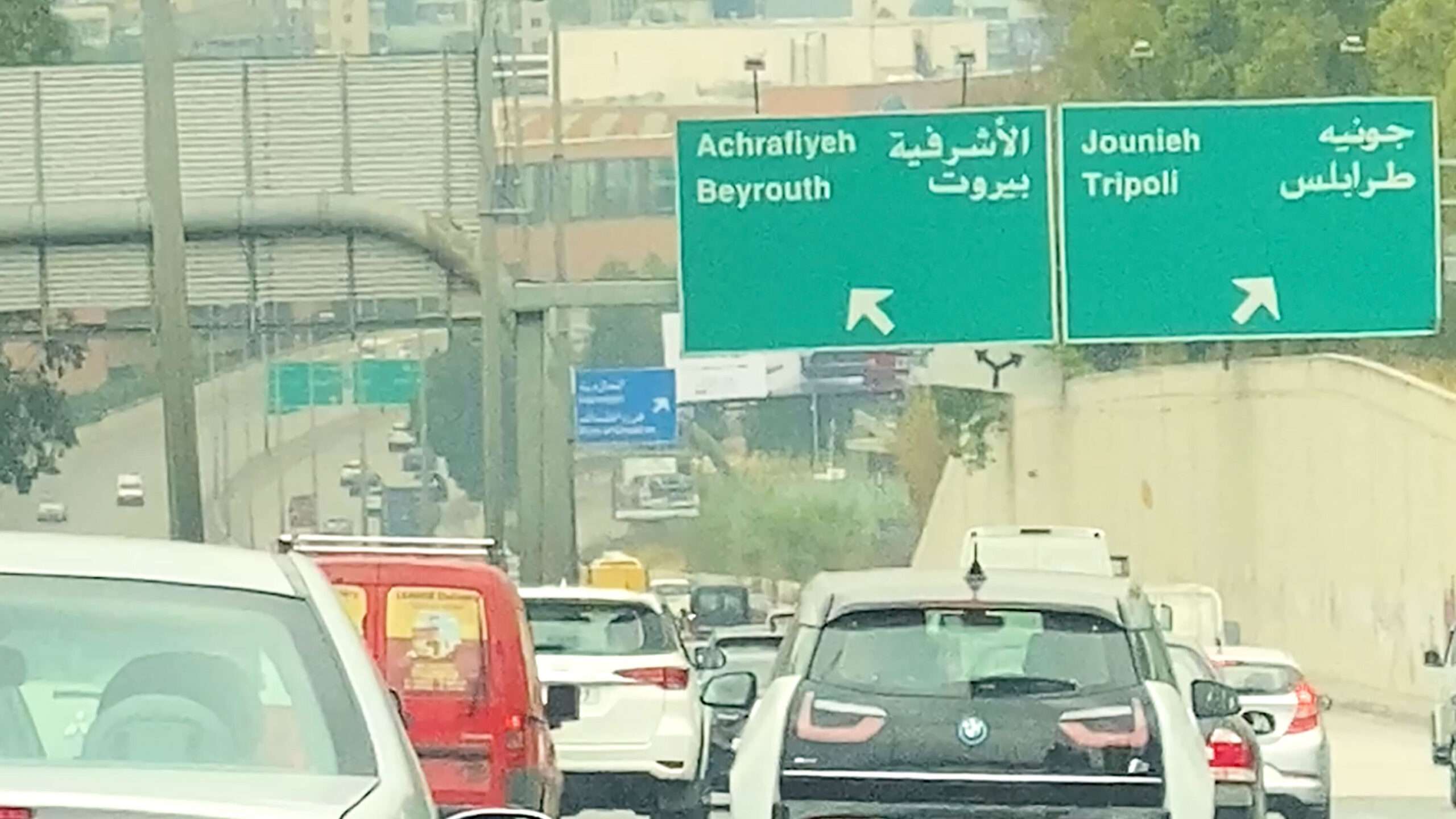

The sketch rings true to anyone who has ever driven in Beirut, where the streets are like a nest of bees you’ve just disturbed. Everyone swerves and stings, rushing in all directions. As a native Beiruti now living in Cambridge, Mass., I try to resist when I visit Lebanon, but I become part of the swarm because the road demands it. Traffic rules are rewritten minute by minute. A taxi driver stops to haggle with a passenger mid-lane while the cars behind wait; a roundabout turns into a duel of bumpers; pedestrians step off the sidewalk to cross a street only to be sped at.

Driving in Beirut is one mundane example of how we Lebanese have stopped believing we owe each other or our unraveling country anything. The road’s swarm logic governs our politics, where elected officials all seem to be rushing ahead randomly. We have no faith in the system, only in our own maneuvering. Heartbreak has become muscle memory.

Driving is an expression of our society’s permanent gridlock, and even a deeper rot: It reveals that we have lost the thread that connects us to one another and that the only way forward is to cut someone else off.

How did we get this way?

Policy failures and broken institutions are partly to blame. Lebanon’s institutions have struggled to recover since the civil war, which raged from 1975 to 1990, leaving an estimated 150,000 dead. More recently, banks froze deposits in the 2019 economic crash, wiping out people’s savings and plunging much of the country into poverty. Months later, the Beirut port blast, one of the largest nonnuclear explosions in history, killed at least 235 people, injured thousands and destroyed a large swath of the capital.

Alongside those disasters, we have experienced a slow, grinding erosion of trust, accountability and basic function. Public services have all but disappeared. ATMs are moody, courts are backlogged for years and government offices operate with little budget or oversight. What remains is a country where dysfunction is the norm and survival depends on workarounds.

But many months later, little has shifted. Hezbollah is still armed, Israel still occupies our land in the south and continues to bomb parts of the country, killing more than 100 civilians since a cease-fire with Lebanon 10 months ago, according to the United Nations. International donors continue to tie meaningful aid for Lebanon’s reconstruction and recovery to the disarmament of Hezbollah and the restoration of full state authority — conditions that Lebanese leaders have failed to meet — and we are still too practiced in survival to believe change could belong to us.

We’re no longer in free fall, but much remains broken. The corrupt are still in place. We are stuck in the rubble, but pretending we’re not. Collapse here doesn’t mean change. It just means adjusting to worse terms. We call it resilience, but at what point does resilience become resignation? When does adapting stop being a strength and start being a trap?

Absurdity flourishes in a country where a few thrive and the rest survive. If you want to see what that looks like, step into Em Sherif Deli. The restaurant sits in Beirut’s glitzy new downtown, with its wide boulevards, manicured medians and luxury high-rises. It feels almost like a different city.

Two countries are living on top of each other, one buffered by generators, drivers and imported everything, the other left to negotiate survival in the margins. What’s most unsettling isn’t how shocking it feels, but how routine it is. Just like we speed through intersections without looking.

On a recent summer drive to the beach with my 15-year-old son, the road wound past the site of the port explosion — the debris has mostly been cleared, but nothing here has been rebuilt — and then past another scar we have stopped seeing: the site where former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was assassinated by a truck bomb in 2005.

My son asked quietly, “Are the people who did it in jail?”

I wasn’t sure which tragedy he was referring to. I let out a short laugh, not because the question was funny, but because it felt so absurd to even ask such a question. Then it hit me: The real absurdity was my reaction. When you stop seeking answers, adaptation becomes a trap. That’s when you realize that nothing ever changes, except how far we’ve lowered our expectations.