Fratricide: The Armenian Church at the Hands of the Armenian Regime

Given such a deep connection, it is more than a bit shocking that the Armenian Church is suffering an ongoing wave of arrests and accusations – personal, partisan, and political – at the hands of the government of the Republic of Armenia. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has not only arrested priests, bishops, and archbishops, he, his wife, and political party have engaged in a harsh war of words with the Head of the Armenian Church itself, Catholicos Karekin II. The roots of this clash between the prime minister and the Church go back years.

Coming to power in the democratic Velvet Revolution of 2018 against corrupt and autocratic rule, the journalist and politician Pashinyan was styled a pro-Western reformer, a product of Western investment in Eastern European civil society in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Russian propaganda says that Pashinyan and his circle are the product of the likes of the Soros Foundation and organizations like USAID and NED. Anti-Russian voices counter that the 2018 revolt was the will of the Armenian people (later ratified in democratic elections won overwhelmingly by Pashinyan). Both sides are telling the truth.

Pashinyan rose to power railing against the so-called “Karabakh Clan,” former politicians who came originally from the Armenian enclave in Azerbaijan and who had risen to high office in Armenia. And yet it was Pashinyan himself who in 2019 would controversially utter the unprecedented statement that “Karabakh is a part of Armenia and full stop!”

As political scientist Kimataka Matsuzato has convincingly argued, it was Pashinyan, more than any other individual, who is responsible for the loss of Karabakh because of a series of disastrous political, diplomatic, and military decisions made by his government. This is a key part of the dispute with the Church.

The Armenian Church has criticized Pashinyan’s governance, on Karabakh and other matters, and the Prime Minister is aggressively seeking to shore up his political position before elections slated to be held in June 2026. He has broad powers of coercion and repression, ironically inherited by him from the autocrat Prime Minister Sargsyan who was overthrown in 2018. Pashinyan has used them ruthlessly against church leaders.

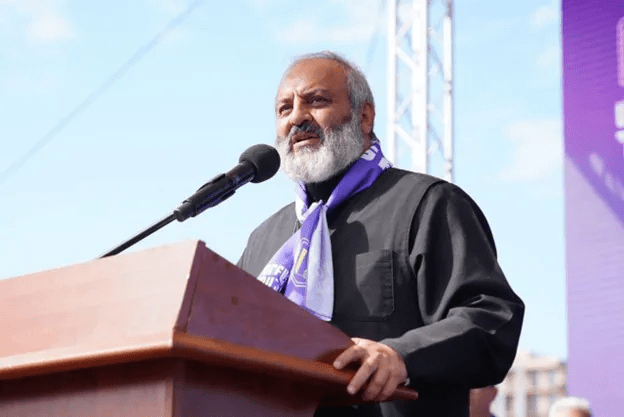

On June 25, 2025, the Armenian government arrested Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan and 13 others, charging them with treason and terrorism in plotting a supposed coup. The charismatic Galstanyan led popular demonstrations against Pashinyan for his Karabakh policies and for handing four border villages in Armenia proper (in his diocese of Tavush) to Azerbaijan. The Prime Minister described the arrests as disrupting a “large and sinister plan by the criminal-oligarchic clergy to take power.” Archbishop Galstanyan’s trial is still ongoing.

On June 27, 2025, the government took into custody Archbishop Mikayel Ajapahyan (they had earlier tried to arrest him on the grounds of Etchmiadzin Cathedral and had been prevented by the people). Charged with attempting to overthrow the government, Ajapahyan was sentenced in September to two years in prison.

On October 15, 2025, six more priests, including Bishop Mkrtich Proshyan, who is the nephew of Catholicos Karekin II, were arrested and charged with “coercing” people to attend anti-government demonstrations in 2021, demonstrations against the government’s policies on Nagorno-Karabakh.

Armenian police gathered to arrest Archbishop Ajapahyan at Holy Etchmiadzin (June 2025)

Looming over the arrests and serving as the backdrop to the campaign against the Church is the August 8, 2025 Armenia-Azerbaijan Peace Deal, an agreement engineered by the Trump Administration which, among other things, aimed at preventing an invasion by Azerbaijan of Armenia. Azerbaijan is still gearing up for war in terms of weapons purchases and bellicose rhetoric but is also holding out carrots as well as sticks. On November 14, 2025, for the first time in 30 years, a grain shipment arrived in Armenia from Kazakhstan having crossed Azerbaijan. Part of the promise of the peace deal is that it would bring not just peace but prosperity (and enhanced regional trade) to Armenia.

In a difficult balancing act, Pashinyan seeks to blame his critics within the Church of being pro-Russian (even though Galstanyan is Western-educated) and of trying to overthrow him while knowing that attacking the Church is generally unpopular and hoping that the deal will improve things quickly enough to matter for ordinary citizens. Meanwhile he faces hostile propaganda from Russia and Iran and principled criticism from Armenians (in and outside the Church) while he tries to blur the difference between the two.

There seems little doubt that the political campaign against the Armenian Church is politically motivated, much of the evidence and charges are trumped up, and that it could turn out quite badly for all Armenians. Pashinyan may not even be thinking just of his own political future but may believe that suffocating opposition is the only way to preserve Armenia in the face of invasion. As one Azeri outlet approvingly noted, “the Church stands in the way” of Pashinyan’s vision. One day soon we will know whether cynicism or self-sacrifice, or a weird combination of both, was the main factor in this campaign. And whether it was actually worth it.

*Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice President of MEMRI.