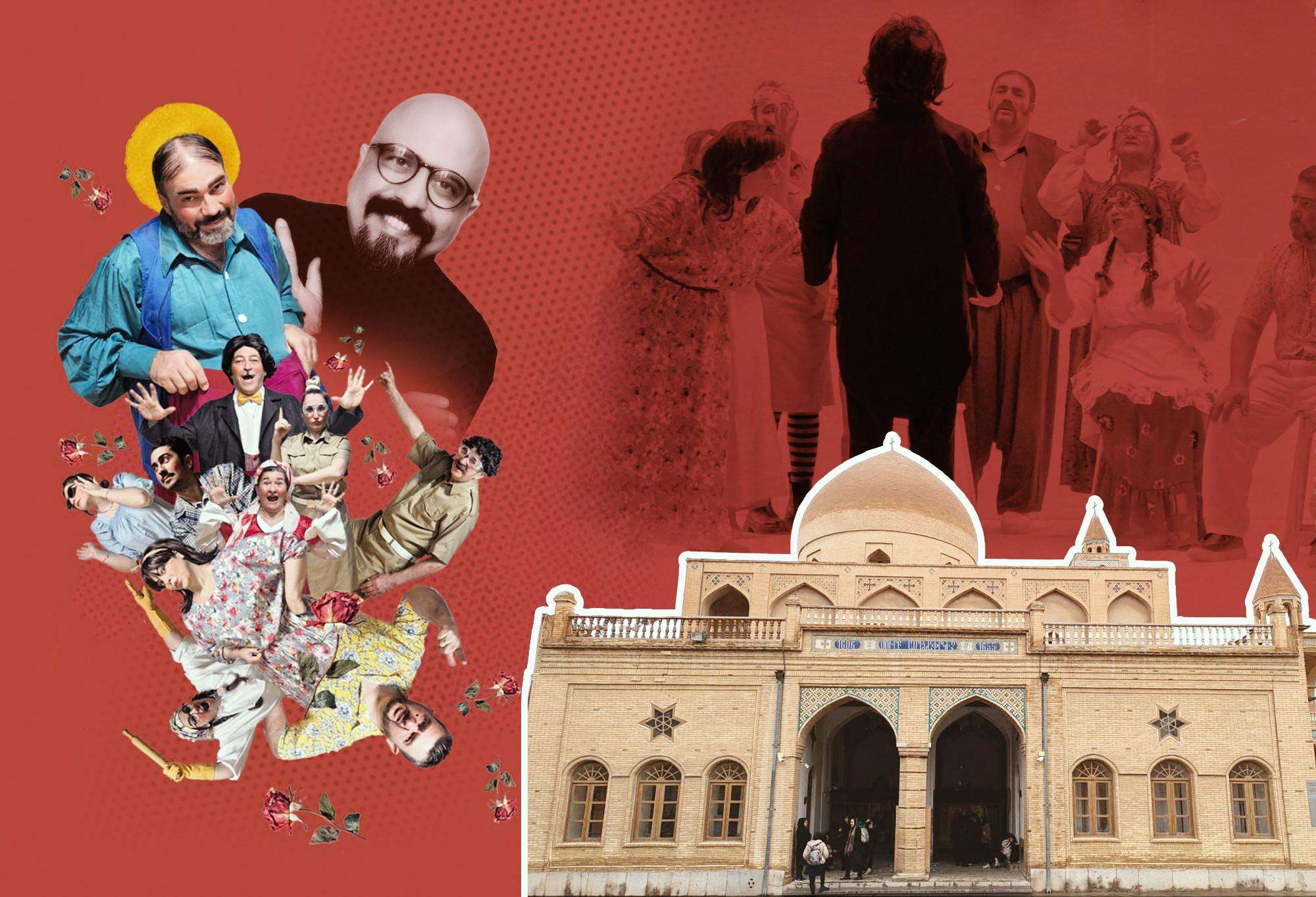

The Revival of Armenian Theater in Isfahan: Molière’s Return After 140 Years

By Nazenik Saroyan

Hetq.am

A security guard calls after me at the gates of the Ararat Club in New Julfa. I greet him in Armenian and receive a nod of approval to enter, a permission rarely granted to non-Armenians. From inside the hall, voices in Persian and Armenian drift out. A rehearsal is underway. The actors discuss the performance in Persian, but the play itself is in Armenian.

At the center of it all is Habib Narimani, the only Persian allowed access to the Armenian community space of Isfahan, a place that operates outside the country’s strict Islamic codes.

One hundred forty years after the first staging of The Doctor in Spite of Himself in Isfahan in 1886, Molière’s comedy returns to the stage at Narimani’s initiative.

Narimani is the artistic director of the Levon Shant Theater Group. For a period, the troupe had no leader. New Julfa was emptying of Armenians, there were no trained cadres, yet the actors were determined to keep the theater alive. The community lacked the funds to invite a specialist from Armenia. Attempts to bring an Armenian director from Tehran also failed. Eventually, it was decided to invite Narimani.

Actors Zarenoush, Haydouk and Zhorzh convinced community leaders to consider his candidacy. They already knew him. Years earlier, he had staged Macbeth with New Julfa Armenians and presented it at a Shakespeare festival in Yerevan. He had also involved Armenian actors in his local projects.

During festival visits to Armenia, Narimani says he experienced Yerevan as poetry and passionate music. A devoted admirer of Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Parajanov, he felt as if he were inside the worlds of their films. The winding roads overlooking Mount Ararat struck him as dizzyingly beautiful. One day, standing before the Armenian National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet, he promised himself he would one day stage a performance in that city.

He accepted the Ararat Club’s invitation to join the community’s mission of keeping Armenian theater in Isfahan alive and training a new generation of actors.

When rehearsal ends, Narimani turns to me and says that modern Iranian theater was shaped under Armenian influence. Even the earliest steps of film production in Iran, he notes, were taken by Armenians.

According to him, Armenian contributions transformed Iranian theater in acting style, dramaturgy, staging, and even auditorium design. Armenian performers, he says, helped bring women onto the stage at a time when women were not even allowed to attend theater as spectators. In the 20th century, the Tabriz-Armenian actress Varto Terian appeared on stage.

“Armenians introduced Iranian dramatists to global authors such as William Shakespeare, Moliere, Ben Jonson, and Anton Chekhov. Productions by maestro Vahram Papazian also served as sparks for change. Before that, Iranian theater largely revolved around ta’zieh religious performances and street shows.

We owe the birth of modern Iranian theater to Armenians,” Narimani says. For that reason, he now wants to support the community so Armenian theater can continue. His goal is not to replace anything, but to restore a living link between past and present.

Although New Julfa’s repertoire has always been multi-genre, it has traditionally leaned toward drama. This time, the Ararat Club wanted to stage a comedy.

“Comedy is a layered and demanding genre. Most of the actors are stepping on stage for the first time. I chose a clear structural framework with movement, rhythm, gesture, and elements of fantasy to help them feel secure and find their place,” he explains.

Narimani’s choice of Molière was also practical.

“Like Shakespeare, Molière can be adapted to any culture. His characters and conflicts can be localized without losing meaning,” he says.

The choice is symbolic as well. The play was among the first European dramas staged in Isfahan in the 19th century, recalling the troupe’s rich past.

Narimani says his aim is not merely to stage a play, but to rebuild confidence among novice actors and within a community that has long lived with caution and retreat. Comedy, he believes, can bring lightness to daily life and teach discipline to actors.

Staging a performance in New Julfa is not so easy for a non-Armenian director. Ararat is an Armenian space, with its own language and written and unwritten rules. During rehearsals, speech constantly shifts from one language to another. He gives directions and cues in one language, while the stage text is delivered in another. Even a slight rise or fall in vocal tone can completely change the meaning of what is said.

He notes that theatrical Armenian itself has layers. The Armenian he heard in Yerevan felt sharper, shaped by geography and perhaps Russian phonetics, while Iranian-Armenian speech carries Persian melodic influence.

“Every rehearsal is a lesson in understanding each other, the play, and how two cultures can meet on one stage,” he says. His time in Yerevan and conversations with Armenian intellectuals helped him grasp a broader Armenian context that he now applies.

The director hopes the performance will also help renew the Armenian-Iranian cultural dialogue in Iran that has at times receded. For decades, Armenian theater functioned mostly behind closed doors. But it was not always so. The same play had been staged in Persian 140 years ago.

Narimani notes that the community’s inward turn did not begin yesterday. Under the Qajars, Armenians, like other minorities, were segregated and later given official minority status. During the Pahlavi era, those lines blurred somewhat, but the Islamic Revolution redrew them more sharply. Armenian performances gradually became for Armenian audiences only.

“Iranians have always seen Armenians as creative and capable people, as their own. Notice that I call them Armenian-speaking Iranians, not migrants,” he says.

Yet the community also turned inward as a form of self-protection and identity preservation, which isolated its art from the surrounding environment.

Narimani now seeks to gently push against those historical boundaries, reopening space for Armenian theater to be part of Iran’s cultural life without losing itself. He hopes to stage the play in Isfahan’s public theaters. Most permits are ready, and he is optimistic the play will be well received beyond Armenian audiences.

In today’s Iran, keeping theater alive is no longer just about art. Continuous emigration weakens casts, audiences shrink, and economic hardship leaves little room for culture. During the 2025 Israeli attacks on Iran, some actors left for safety in Armenia.

“We decided not to stop rehearsals,” Narimani recalls. “In those uncertain days, stage work became an escape from fear, bombings, and air raid sirens. We continued rehearsing under the sounds of anti-aircraft fire.”

A comedy might have seemed strange for anxious nights, but it was also necessary.

The Armenian community has already seen the performance and laughed wholeheartedly. When the curtain rises for Persian audiences, the play will not be just a comedy. It will be a sign that Armenian theatrical art is returning to the Iranian stage, proving that art can cross boundaries drawn by politics.

Photo by Nazenik Saroyan; play photos provided by Habib Narimani.