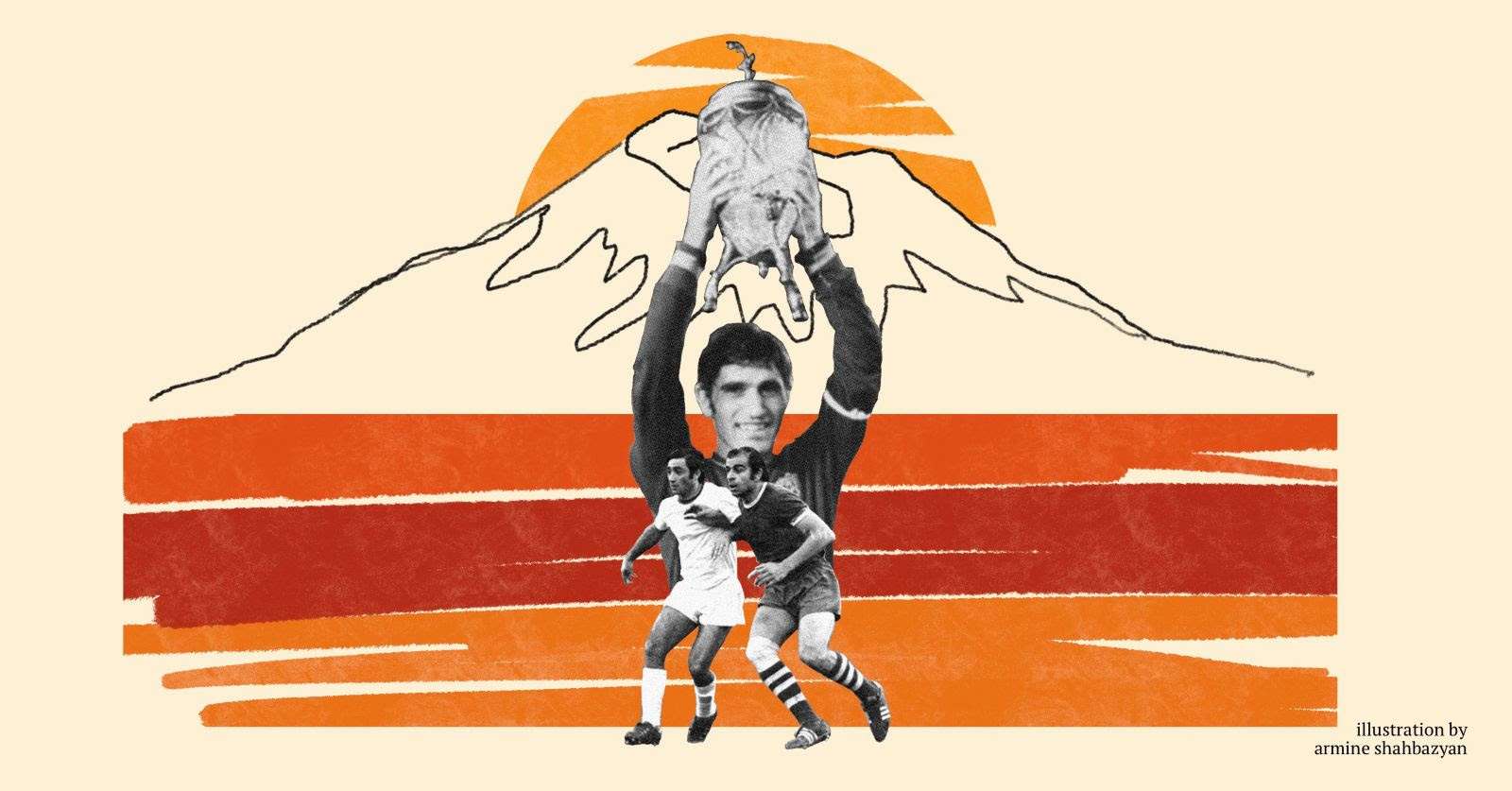

Ararat-73 and “Apricot Socialism” Why Armenians Still Celebrate a Football Team That Transcended Sport

A Russian-made film titled “Golden Double” is arriving in Armenian cinemas. The film dramatizes FC Ararat Yerevan’s legendary 1973 season. It is an interesting choice of topic, given the current state of Russian-Armenian relations. Many Armenians feel betrayed by Russia, so this film may seem like a last-minute attempt at soft power. However, production of the film began long ago, and the film was most likely conceived as an homage to the legendary team rather than soft power. Whatever the case, it’s worth remembering what “Ararat-73” was and what made it famous.

Ararart-73 holds such importance for Armenians that in October 2016, a bronze monument to the team was unveiled — life-sized statues of the squad cradling a replica USSR Champions Cup. It isn’t the only memorial to Ararat-73. There is another one in the village of Agarak in Aragatsotn and even a bestselling book released in 2023, called Ararat-73: The Golden Age of Armenian Football, by Suren Baghdasaryan, a former TV and radio commentator who covered most of the legendary team’s matches in 1973. The book includes detailed match reports, player interviews and memoirs from FC Ararat Yerevan’s glory days. Its success was followed by a book from Georgian historian Davit Jishkariani on Dinamo Tbilisi, the club that played much the same role for Soviet Georgia as Ararat played for Soviet Armenia. Another perspective comes from Arsen Kakosyan’s The Night After Football: A Supporter’s Diary, first published in Russian in 1974 and reissued in Armenian in 2023, capturing the fervor from the stands.

Why honor an almost 50-year-old football squad with bronze statues and books? Why does Ararat-73 loom so large in the Armenian psyche? To understand this, we need to understand the context in which Ararat played: late Soviet Armenia, a period some scholars have called “Apricot Socialism”. Armenia had no national team then, it was still a Soviet republic, not an independent state. Yet Ararat’s double victory ignited a fire that burns decades later. Ararat became more than a club: it was a rallying cry for national identity. And as the collapse of the USSR brought difficult times, Ararat-73 also became a memory of the relatively comfortable life under late socialism.

Ararat Yerevan: The Poster Child of “Apricot Socialism”

The Ararat-73 phenomenon emerged from the convergence of sport, Armenian national sentiment and Soviet policy. The connection between sport, especially football, and national identity is well established. As scholar Eric Hobsbawm observed, sport is a “uniquely effective medium” in which “the imagined community of millions seems more real as a team of eleven named people.” In imperial and multi-ethnic states like the USSR, football carried even greater weight.

There is still no consensus on what the Soviet Union ultimately was: an oppressive colonial empire or a voluntary association of nations pursuing a shared socialist project. The truth likely lies somewhere in between. Scholars such as Vahakn Dadrian, Ronald Suny and Razmik Panossian have examined the relationship between Soviet nationalities policy and Armenian identity. What emerged was what some describe as a “Second Republic” — not an independent state, but a political entity with many of its attributes. Particularly in the post-Stalin era, it functioned as a relatively protected space where Armenian culture and identity could endure and evolve within the constraints of the Soviet system. Sport, and football in particular, played a significant role in sustaining that interplay.

The USSR’s sports system mirrored its mixed nationalities policy. It used sport and physical culture to promote “the Soviet way of life” and forge a unified Soviet patriotism. Yet Soviet sports also allowed relative freedom for expressing local cultural identities. Football stood out. The state heavily promoted it as a vessel of Soviet patriotism, but fan culture often slipped into subtle rebellion; unpredictable and risky for authorities. Teams from non-Russian republics channeled national pride. Fans rallied around local clubs like Ukraine’s Dynamo Kyiv, Georgia’s Dinamo Tbilisi, Azerbaijan’s Neftchi, and Armenia’s Ararat. Cheering these teams offered a safe outlet for nationalist fervor. Soviet republics lacked official national teams, but their top football clubs filled the gap in the USSR league. Fans saw the Soviet Championship and Cup as epic clashes not just between city squads, but between republics and ethnic groups.

Ararat Yerevan fits this pattern. Its victories coincided with a period that can be described as a “National Revival” in Soviet Armenia. This was arguably the high point of the Soviet era in Armenia, when a balance was achieved between national identity and cultural specificity on the one hand, and integration into the larger Soviet system on the other. German scholar Maike Lehmann has called this mix “apricot socialism”. Ararat’s rise took place during the years of the “Thaw” and immediately after, when “stagnation” had not yet become that obvious. The Soviet government became less controlling, and the economy, while lagging behind capitalist countries, created a relatively comfortable environment for most Soviet citizens. Many Soviet citizens, at least the ones who did not actively oppose the regime, enjoyed a calm and predictable life, along with a certain level of freedom of thought and expression, albeit quite limited. This period has created much nostalgia for the Soviet times. And it was precisely during these years that Ararat Yerevan brought so much joy to its supporters.

From Spartak to Ararat-73

So, I’m already halfway through the article and still haven’t written anything about actual football. Time to correct that. Ararat Yerevan’s story began in 1935, when Spartak, Yerevan’s first professional football team was established. In 1936, another club emerged: Dinamo. The two merged in 1937 as Dinamo, keeping that name until 1954. Then it switched back to Spartak until 1963, when it became Ararat for good.

The history of the club’s renaming is important. According to Baghdasaryan, credit goes to Varazdat Khachikyan, who chaired Armenia’s Sports Council at the time. Whatever the backstory, it marked a bold symbolic pivot. The previous names, Spartak and Dinamo, screamed Soviet ideology. Spartak referenced class struggle, evoking Spartacus, the Roman slave rebel idolized by early socialists. In the USSR the name branded clubs and major sporting events (“Spartakiada”). Dinamo was a nod to dynamo, a machine for generating electricity that symbolized industry and modernization. It named powerhouses like Dinamo Kyiv, Tbilisi, and Moscow (originally the secret police’s squad).

The name Ararat was worlds apart. It referenced Mount Ararat, for many Armenians the eternal emblem of the national soul, or in academic terms, a key part of the “myth-symbol complex” (a term coined by British scholar A.D. Smith) of Armenian national identity. The name also evoked memories of genocide and the loss of historical homeland, at a time when demands for genocide recognition were becoming central to Armenian national revival. Renaming the team tapped straight into Armenia’s 1960s national awakening. Armenia wasn’t alone in this trend: across Soviet republics, football clubs were becoming rallying points for local pride (Dinamo Tbilisi, for example).

The name change may have helped the club. It had enjoyed success before. In 1949, as Dinamo, it broke into the Soviet Top League for the first time. The next decade was a rollercoaster of big wins and brutal defeats. In 1954, Spartak hit its stride, reaching the USSR Cup final before falling to Dynamo Kyiv. But it was only in 1965, now under the name Ararat, that the club secured its place in the Top League and stayed there until the USSR’s collapse in 1991.

Ararat’s Golden Era

By the early 1970s, Ararat was one of the strongest teams in the Soviet Top League. The team’s stars included Arkady Andriasyan, Levon Ishtoyan, Hovhannes Zanazanyan, and Alyosha Abramyan. Among them were Sergey Bondarenko, born in Ukraine, and Alexander Kovalenko, born in Russia’s Sverdlovsk region — both grown up in Armenia and were seen as “true Armenians” by the team’s fans. Soviet Armenia’s sports bosses also sought talent in other USSR republics, especially among ethnic Armenians. Some of Ararat’s most noted players came from Baku’s Armenian community, including star striker Eduard Margarov. The coaches were equally diverse: locals, Armenians from other republics like Artyom Falyan (from Baku) and Nikita Simonyan (from Moscow), and outsiders such as Nikolay Glebov, Viktor Maslov, and Nikolay Gulyayev. During the 1973 championship, Russia-born Armenian Nikita Simonyan, a Spartak Moscow legend and Soviet national team veteran, took the helm.

In 1971, Ararat came in second in the USSR championship. But 1973 marked the team’s greatest triumph: sweeping both the USSR Championship and Cup. The Cup final against Dinamo Kyiv, Ararat’s top league rival, delivered the drama. Dinamo controlled most of the match, leading 1-0 at the 89th minute. Then Ararat striker Levon Ishtoyan scored, tying it up. In extra time, he scored again at the 103rd minute, clinching victory. The jubilation in Armenia after this win was so widespread, that local Communist bosses worried it could spiral out of control. To give people some time to calm down, Ararat did not return to Yerevan immediately but was flown to Donetsk for a championship game against Donetsk Shakhtar (which it also won).

When Ararat returned from Donetsk, Yerevan erupted in celebration. Sergey Poghosyan, one of Ararat’s players, remembers landing at the airport in Yerevan to utter chaos, where crowds had gathered to greet the team. In Baghdasrayan’s book, he described looking out the airplane window and seeing a sea of people below, some perched on rooftops. Cheering crowds lined the roads, stretching the usual 15-minute drive from the airport to city center into a two-hour crawl. An elderly couple even blocked traffic with a table, demanding the players share a drink before letting them pass.

Araratmania peaked at the USSR Championship final round on October 28, 1973. Ararat was playing against Zenith Leningrad, but the real rival was Dynamo Kyiv, which was playing Kayrat Almaty in Kazakhstan at the same time. A win against Zenith would seal Ararat’s championship. Some 100,000 fans packed Hrazdan Stadium and beyond. The pre-game atmosphere was electric — music, dancing, zurna, dhol, duduk and clarinet blaring from the stands, folk dancers in traditional dress. Ararat won it 3-2. But fans already knew Dynamo Kyiv had lost to Kayrat Almaty, so celebrations erupted mid-game. What followed was a pan-national blowout. Back to Poghosyan’s interview: “Impossible to describe the stadium chaos. Fans sat on newspapers; at the whistle, they lit them as torches, igniting the whole place and sky…We stood on the pitch watching it burn. Dangerous? Sure. But pure national frenzy, no one dared stop it.”

Diaspora Armenians were also a part of the Ararat-73 cult, even though following the Soviet Armenian team wasn’t easy for them. In 1973, a group of Armenians from Lebanon came to support Ararat in Yerevan and in Moscow. Their presence helped secure Armenian language commentary for the Cup finals match against Dynamo Kyiv. As Baghdasaryan recounts in his book, Armenian fans pushed for native-language radio coverage in the run-up to the match, but the budgets were exhausted and officials refused extra funds, arguing that Moscow TV would air it anyway. The Lebanese Armenians, who had traveled to the USSR specifically to support Ararat, stepped in to resolve the issue. They lobbied Armenia’s Sports Committee, creating the perfect justification for an Armenian-language broadcast. Later, when Ararat played a Champions League match against Celtic in Cork, Ireland as the USSR champion, many Diaspora Armenians attended the game, mostly from Britain and France.

After 1973, Ararat never recaptured that magic. Still, the club remained among the USSR’s elite throughout the 1970s, winning the Soviet Cup again in 1975 and taking silver in the 1976 Championship. Europe proved tougher — their best run came in the 1975 Champions’ Cup quarterfinals, where they won at home but lost in Munich to eventual champions Bayern. Through the late 1970s and 1980s, they remained in the top Soviet league, finishing seventh in the final 1991 championship. When Armenia gained independence and fielded a national team competing in European and world tournaments, fans shifted their passion there. Domestic league games drew far less interest.

Yet “Ararat-73” lives on as a legend. To me, it’s a powerful symbol of “apricot socialism” — Soviet Armenia’s unique mash-up of national pride and Soviet loyalty. I have my own personal reasons for cherishing both the football team and the term. I don’t remember much from my Soviet Armenian childhood, but I do remember apricots were tasty, my family seemed happy, and a bright future seemed to lie ahead. Sometimes my father or grandfather would sit in the living room with their friends, watching football on that huge old TV with only three or four channels. Usually, they would yell angrily at players who missed the chance to score, or make sarcastic jokes about them. But then, finally, one of “our guys” would score, and that was pure jubilation. Born in 1980, I missed Ararat’s 1973 triumph. But remembering my parents and their friends cheering for the Armenian team is one of the sweetest memories of my childhood. Even though I wasn’t there, I think I understand perfectly what it meant to be an Ararat fan more than half a century ago. Thank you, Ararat Yerevan, for those warm memories!