Armenia’s Church-State Standoff: A Battle of Attrition with No Clear Victor

Caucasuswatch.de

The ongoing confrontation between the Armenian government and the Armenian Apostolic Church has now stretched for several months, marked by criminal investigations, clergy arrests, leaked recordings, and intimate videos made public.

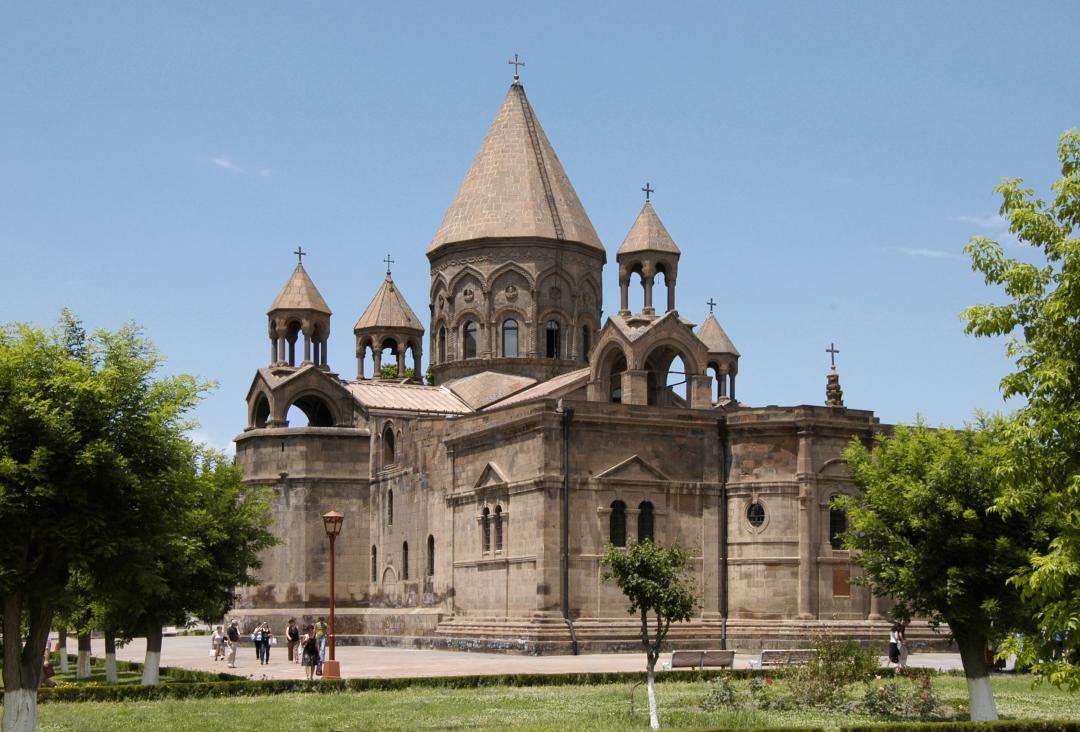

For months now, Armenia has watched an unusual standoff unfold between its government and its oldest national institution. Intimate videos have surfaced. Wiretapped conversations have been published. Clergy have been detained and charged. Prime Minister Pashinyan has made it a point to attend masses under priests suspended by the Catholicos—services that can scarcely be considered normal religious liturgies. At the same time, advocates of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin have gathered in numbers to prove their loyalty.

An unexpected development came on November 27, when nine bishops met with Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan. The bishops had earlier signed a statement suggesting the Catholicos’s conduct was incompatible with Church canon law. And yet, neither has achieved what it needs: a groundswell of public support that can force the issue to close.

The Arithmetic of Low Approval

The explanation, according to analysts, lies in the arithmetic of approval ratings. Both the government and the Church leadership enter this conflict from positions of relative weakness.

“If Pashinyan had initiated this process right after the revolution, when he enjoyed 80 percent support, there wouldn’t be a problem mobilizing people,” observes Tigran Grigoryan, a political analyst. “In the case of the Church, it’s obvious that the hierarchy is quite corrupt—that was never really a secret to anyone in Armenia.” This mutual vulnerability creates an odd equilibrium. The government lacks the overwhelming public mandate that would make challenging such a venerable institution politically costless. The Church hierarchy, meanwhile, cannot rely solely on the popularity of its leadership to shield itself from scrutiny.

Recent polling data from the International Republican Institute illustrates this complex picture. The Armenian Apostolic Church has experienced notable fluctuations in public trust since 2021. In February of that year, overall favorable views stood at 52 percent, while unfavorable views reached 44 percent. By early 2023, satisfaction had climbed to 54 percent, making the Church the most trusted institution among those surveyed. But by September 2024, approval had slipped to 48 percent, with disapproval nearly matching it at 46 percent. The most recent data (2025 June), however, shows a significant rebound: approval surged to 58 percent, with only 35 percent expressing disapproval. This places the Church second only to the Armed Forces, which commands 72 percent approval, among Armenia’s most trusted institutions.

Is an Institution a Leadership?

Yet these figures require careful interpretation. As Grigoryan notes, there is a crucial distinction between attitudes toward the Church as an institution and feelings about its current leadership.

“Everyone accepts the Church as an important national structure,” he explains. “But attitudes toward the Catholicos are far more ambiguous. If the Catholicos enjoyed broad public support, Pashinyan would never have been able to start this process in the first place.”

He draws a pointed comparison: “I find it hard to imagine any government in Georgia ever daring to initiate this type of process against the Church there. Though it’s not clear which situation is actually better in my view, ours is, because over there the fanatics dictate the public agenda.”

Narek Sukiasyan, political scientist and a visiting postdoctoral fellow at the University of Zurich, offers a more cautious reading of the polling data. Following the 2020 Second Karabakh War, he notes, there was a notable decline in public trust toward the Church, a trend reflecting both disillusionment and collective depression, with many feeling the institution had failed to meet expectations during the national crisis.

“The IRI polls too suggest this post-war decline followed by a significant spike after the start of the ruling party-church conflict,” Sukiasyan observes. “Since the largest demographic support group of the Church is young people – a rather odd phenomenon – we may hypothesize that the spike is not a proof of religious preferences but a show of political consolidation around the Church.” He adds a telling piece of anecdotal evidence: “I have been witnessing many of my atheist friends frustrated with what the ruling party does.”

A Strategy of Attrition

The government’s approach appears designed for the long game. Rather than seeking a dramatic confrontation, authorities seem intent on gradually wearing down resistance through sustained pressure. “The ruling party is escalating slowly to unlock new levels of contention that can be acceptable for the wider public, and with every step to normalize a new level,” Sukiasyan explains. “But they haven’t yet amassed the critical mass of support needed to push the process to its endgame.” This strategy has two main components. The first involves legal mechanisms—criminal cases against various clergy, with the possibility of charges against the Catholicos himself, given that an investigation based on leaked recordings is already underway.

The second component is more symbolic: Pashinyan’s weekly appearances at liturgies led by clergy willing to defy the Catholicos, demonstrating that divisions exist within the Church itself.

The Church, meanwhile, has adopted what Sukiasyan characterizes as “strategic retrenchment,” a markedly low-profile posture that makes rapid escalation difficult. “Escalation takes two,” he notes, “and the ruling party has historically been most effective when a pressured or vulnerable opponent lashes back. Sensing this, the Church seems intent on avoiding exactly that dynamic—perhaps hoping the controversy will fade on its own or at least survive past next year’s parliamentary elections.”

Human rights and rule-of-law organizations have raised alarms about what they view as the politically motivated use of law enforcement. “The authorities are trying to cloak this campaign in the language of legalism, though not very convincingly,” Sukiasyan observes. “When political pronouncements from top leaders repeatedly align, almost beat-for-beat, with subsequent law-enforcement actions, it becomes difficult to dismiss the impression of deliberate orchestration.”

Elections, Europe, and Geopolitical Realities

The timing of this confrontation is no accident. With parliamentary elections scheduled for 2026, the Church represents one of the few major institutions not yet under the ruling party’s control and one capable of articulating alternative political positions.

“The Church continues to be a large institution, perhaps one of the only ones not under the executive’s control,” Grigoryan notes. “The fact that there are structures that can express alternative views and potentially participate in opposition politics probably prompted them to try to neutralize that threat before the elections.”

Whether resolved before voting day or not, the conflict will almost certainly become a campaign centerpiece. “Should it persist into election season, the ruling party will inevitably frame the mandate it seeks as public endorsement for taking more forceful action,” Sukiasyan predicts. “The narrative will not be limited to accusations of violating the celibacy oath; it will also hinge on portraying the Church’s leadership as conduits of illicit Russian influence.”

This framing connects to the government’s stated European aspirations. Yet Grigoryan is skeptical about the substance behind those aspirations. “The EU integration process is not serious right now—there is no serious EU membership agenda at this point,” he argues. “It’s more of a pre-election agenda. It’s hard to talk about EU integration when you’re still part of the Eurasian Economic Union, and trade with Russia has doubled over the past two or three years. The structural realities show where actual policy is moving.”

Interestingly, Western policymakers may view the Church-state conflict through a different lens than domestic observers. “There also appears to be a measure of quiet empathy among some Western policymakers, who interpret the situation through the more familiar matrix of church-state politics in Ukraine, Moldova, or Georgia,” Sukiasyan notes. “As a result, they may be less critical of the ruling party’s approach than many observers at home might expect.”

As for the peace process with Azerbaijan, Grigoryan doubts the Church conflict will prove decisive. Last year’s movement against delimitation, which had at least tacit support from Church leadership, gained initial traction but faded quickly. “The Church couldn’t play a serious spoiler role even without these actions against it,” he assesses. “The main reason for this conflict is domestic politics.”

Snap Elections: Unlikely but Not Impossible

Speculation about early elections has circulated since late summer, intensifying after the Washington agreements when the ruling party may have sensed a politically advantageous window. Both analysts, however, consider the scenario unlikely. “With only eight months left until scheduled elections, I simply don’t understand the logic of calling early ones,” Grigoryan says. “It would probably benefit the authorities since they’re better prepared, but I believe they’re preparing for regular elections.”

Sukiasyan concurs, though he doesn’t dismiss the possibility entirely. “I don’t consider the likelihood of snap elections to be high, but I also cannot deny them,” he says. “If snap polls do occur, the Church-government issue will certainly be woven into the government’s legitimizing narrative.” He notes that early elections typically favor incumbents, who can time the vote for maximum advantage while opponents scramble. “The opposition remains fragmented even without the added pressure of early elections, offering no coherent plan, proposal, or agenda distinct from the approaches that have failed repeatedly over the past seven years.”

A Society Turned Inward

Perhaps the most telling sign of where this conflict is going isn’t the behavior of the lead characters themselves, but rather the muted response of a broader public. “Over 60 percent of the population doesn’t support any political force,” Grigoryan observes. “This may continue to push people away from politics. Perhaps that’s even one of the goals—to show that politics is a sphere one should stay away from.”

The confrontation, with its leaked recordings, crude language, and published intimate videos, may be reinforcing precisely this disengagement. Both the government’s core supporters and its determined opponents remain entrenched in their respective positions, living in what Grigoryan calls “bubbles”—closed groups where changing minds proves nearly impossible. For now, Armenia’s church-state standoff continues its slow burn—while the broader public, exhausted and disengaged, essentially looks away.

Contributed by Ani Grigoryan, the founder and editor of CivilNetCheck—a fact-checking department at CivilNet online TV.