Film: The woozy beauty of ‘Lullaby for the Mountains’: On Béla Tarr, Armenian landscapes, and the cinema of drifting

Director Hayk Matevosyan and producer Luiza Yeranosyan talk about shaping a wordless debut across Armenia’s highlands, embracing Béla Tarr’s influence, and trusting dreams to carry the film

As the writer-director-

For a while he considered spelling things out. “I had ideas of having some voice-over narration during the editing stage,” he admits. “I eventually understood that I wanted to rely fully on the visuals and soundscape to carry the film’s rhythm.” The task then was to make that rhythm coherent. “I’d say the hardest part of the editing process was finding the right tempo for the scenes and figuring out how those scenes could intertwine on a more dramaturgical level and make sense in the world I created.”

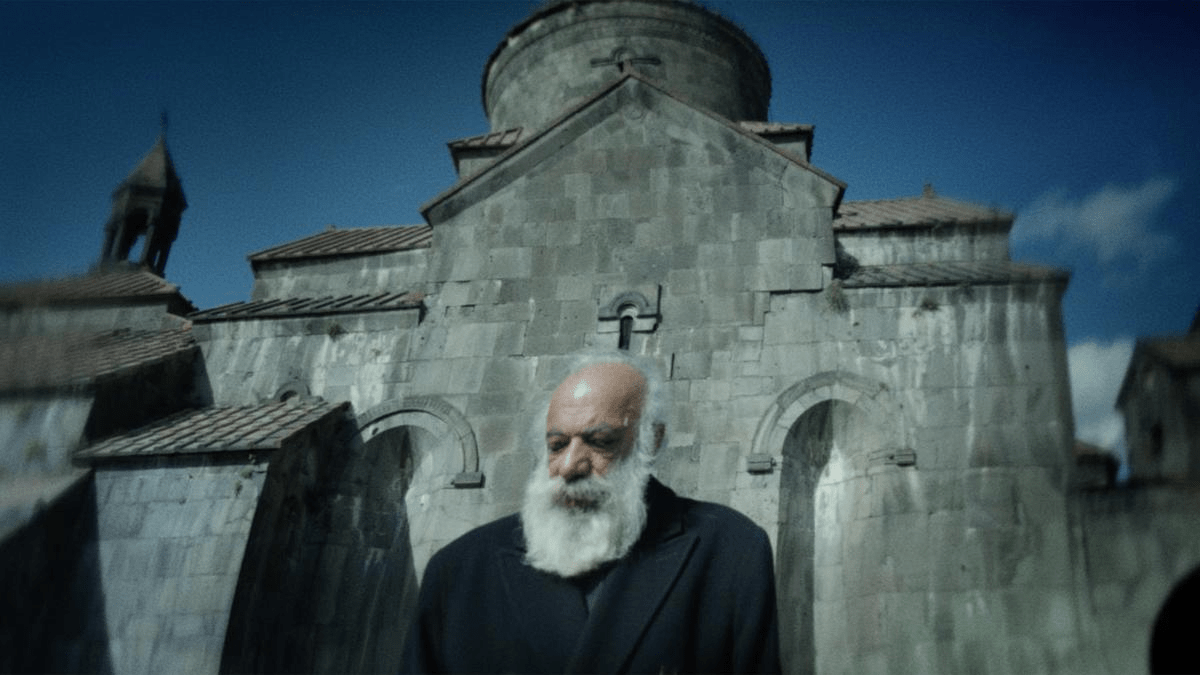

That world is made of churches hollowed by centuries, alongside gravestones, plateaus, and underground passages that predate him. Walking into these Armenian landscapes, he admits to have felt a commitment beyond his own story. “Of course, I do feel an obligation,” he says. “Whenever we were in a specific location, we wouldn’t just jump into filming. My filming style is a bit different. I like to spend time in the place, and that’s what I actually learned from Béla Tarr. He would encourage you not to rush and just be at the location. He’d say that the location is one of the most important characters of the film.”

On many days, the crew was simply father, son, and camera. One of the film’s most tender images came out of that waiting, shot in the village his grandfather comes from, where his father lies sleeping on the ground. “That scene came to be on the spot; it was a very spontaneous moment where both my father and I felt like we wanted to lie down on the land,” Hayk recalls. “I put the camera in between us and just filmed my father asleep, hugging the land.”

He had never worked as a cinematographer before — on shorts and music videos he relied on his longtime collaborator Justin Richards. When Richards could not travel to Armenia, Hayk picked up the camera himself and brought him back in later as the film’s colorist. “That stage of post-production is creatively very important for me, since you start looking at the images as a painter,” he says. “Working with Justin on it was like looking at a clean canvas and re-coloring scenes to give a new, more surreal, dreamy tone to the visuals.”

The dream logic is reinforced in-camera, and the occasionally funny warped distortions of a leaning horse and elongated bodies, come from somewhere more private. “The idea of using distorted lenses and having the landscape and characters appear more elongated and warped came from my dreams,” he says. “The dreams I see usually have visuals that are distorted, much like in the film, so I kind of wanted to recreate the images in my film as close to my dreams as possible.”

In this scheme, people belong to the terrain. “In the film the people or they might even be spirits, are like landscapes,” he says. “For me, the human face is as interesting as a landscape, so there were shots in the film that I tried to juxtapose the human face with the landscape or ancient churches. And using wide lenses even for close ups helped to get a very unique way of seeing the tactile emotional state of the face and eyes.”

Hayk’s scepticism toward film-school orthodoxy is shaped by two names that loom over the project: Werner Herzog and Béla Tarr. He met the legendary auteurs in different corners of the world. “With Werner, it was in 2018 in a Peruvian Jungle, where we made a short film under his guidance. And in 2019, I made another short in Locarno under the mentorship of Béla.” While their methods may have diverged, what stayed with him was their core ethic. “What both of them have in common and constantly would tell is to not wait for the right time to make a film, and to not follow specific industry-set rules on how to make a film. They would always push for risk-taking.”

Producer Luiza Yeranosyan, his partner at Dolly Bell Films, applied that lesson to the budget. “Our method for this film was a bit unorthodox,” she says. “Hayk had a very clear vision and a passion to make this film, and he had a specific time frame in which he wanted to make it. Instead of taking the route of applying and waiting for government or public funds, we financed the film through our company, and also secured private investments.”

They spent time with locals in every part of Armenia they visited, moving through places that were already part of Hayk’s map from childhood trips with his father. “There was a mutual respect when filming — respect toward the people, toward the land, and toward the ancient sites and churches. The film is a love letter to Armenia, to the culture, to the land itself, so there was no other way than to allow the people and the land to accept us first before we even started filming any shots.”

Even now, days later, I catch myself wafting back to that room in Panjim, with the faint echo of chants, and memories of those vignettes of man curled into the earth. And sure, if I did drift off for a chapter or two, Lullaby for the Mountains never held it against me, which might be the most generous thing a film can do.

Lullaby for the Mountains was screened at the 56th International Film Festival of India in Goa.