How Hawaiian monument was misrepresented as first Armenian Genocide memorial in Istanbul

· December 8, 2025

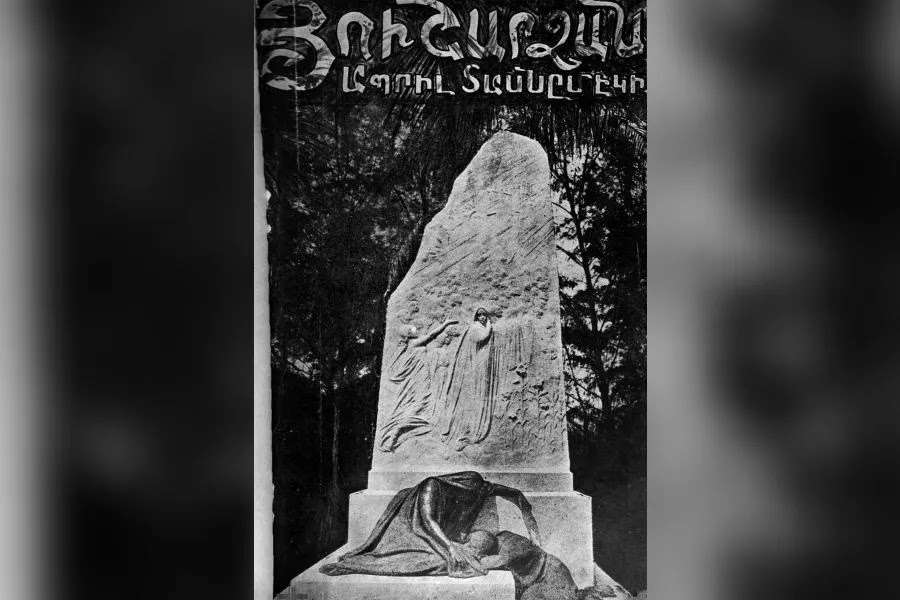

Many of us are familiar with the photograph often described as the “first Armenian Genocide memorial,” supposedly erected in Constantinople. At first glance, it seems to fit the bill: a lifeless woman lying down on the floor, ghostly figures rising behind her like resurrected deportees, and the tropical foliage and palm trees in the background. Wait, tropical foliage and palm trees? Now, that seems out of place, considering this was supposed to be Constantinople.

Turns out, this is not what we’ve been led to believe. In fact, this monument still stands, not in Turkey, but on the Hawaiian island of Kauai. The mystery of this memorial, which we will soon explore, can be declared resolved. The question does remain, however:

How did a monument in the middle of the Pacific Ocean come to be mistaken for one in Constantinople?

For years, the monument was believed to have been erected in 1919 in what is now Gezi Park. At the time, Gezi Park was the Armenian Cemetery of Pangalti, belonging to the nearby Surp Hagop Armenian Hospital. In the 1930s, the cemetery was confiscated by the Turkish state and a park, along with several hotels, was built on its grounds.

Front and back of the postcards distributed by the Committee for the April 11 Commemoration. The postcard version features an added inscription at the base of the monument reading “April 11 (24) Monument (Ապրիլ 11ի Յիշատակարան)” — which does not appear in Teotig’s version. The reverse side bears the stamp of the Committee for the April 11 Commemoration (Ապրիլ 11ի Սգահանդէսի Յանձնախումբ).

The photograph, which purportedly shows some kind of monument, was made famous because it appeared on the cover of Teotig’s Memorial to April 11 (Hushartsan), a book honoring and documenting the intellectuals who perished during the Armenian Genocide. Notably, this book was sponsored by the Committee for the April 11 Commemoration (Ապրիլ 11ի Սգահանդէսի Յանձնախումբ). Formed in Constantinople in 1919 and chaired by Patriarch Zaven Der Yeghiayan, the committee operated in the relatively freer environment created by the British occupation of the city, organizing events and commemorations for the victims of the Armenian Genocide. Among these activities were sponsoring Teotig’s book, holding a memorial service at Pera’s Holy Trinity Church, declaring days of remembrance at Armenian schools and publishing commemorative postcards, with proceeds dedicated to the families of the deceased.

It was this same committee that featured the photograph on Teotig’s book and on its commemorative postcards. As these materials circulated throughout the world, the image of the monument became nearly ubiquitous.

But something didn’t add up.

If such a monument had truly been built, why was there no press coverage? In fact, we can safely say that no contemporary newspaper provides any record of its construction or unveiling.

Erecting such a monument would have been an extraordinary event. One would expect a major ceremony attended by well-known figures replete with speeches, photographs and newspaper reports. Yet, the archival record is silent.

The Rice and Isenberg Monument as it stands today in the Lihue Cemetery in Kauai, Hawaii

The Rice and Isenberg Monument as it stands today in the Lihue Cemetery in Kauai, Hawaii

In fact, even a simple Google reverse image search — like the one conducted by my friend Harry Kezelian — can point in the right direction to the real story. It was actually Harry who first told me that the monument was in Hawaii, a revelation later confirmed in his conversation with Dr. Davidian.

Strangely enough, this revelation has not yet been made public outside scholarly circles, or published in an open-source article — until now.

The monument as first publicized, and likely first photographed, in the October 3, 1911 issue of the Garden Island (Kauai)We may never know exactly when or how the committee came across the photograph of this Hawaiian gravestone. What we do know is that the earliest image appears in a local newspaper: the monument was unveiled on 1 September 1911, and the first published photograph appeared in the 3 October 1911 edition of The Garden Island.

The monument as first publicized, and likely first photographed, in the October 3, 1911 issue of the Garden Island (Kauai)We may never know exactly when or how the committee came across the photograph of this Hawaiian gravestone. What we do know is that the earliest image appears in a local newspaper: the monument was unveiled on 1 September 1911, and the first published photograph appeared in the 3 October 1911 edition of The Garden Island.

The same image appeared in a 1922 issue of the paper announcing the death of the monuments sculptor — a key-figure whose story we will return to shortly. While the photograph used by the committee closely resembles the one in the newspaper in terms of shadow placement, it differs in notable ways: it is adorned with wreaths and flowers.

However, another photograph uncovered by Dr. Tongo of this monument appeared in the 15 June 1914 edition of The Studio, a London-based art magazine. This photograph matches exactly with the famous one Teotig and the April 11 Committee both used in Hushartsan publication and the commemorative postcards.

At the time of this magazine’s publication, Teotig was still in Constantinople, working diligently to publish the next Amenuyn Daretsuytse. The June edition of The Studio may have reached Constantinople at that time, though it may just as well have circulated there in the post-War period.

Moreover, it remains uncertain whether The Studio was the only magazine to publish this photograph — other periodicals may also have featured Sinding’s monument.

The Isenburg Monument as shown in the 15 June Edition of The Studio, a London-based art magazine

The Isenburg Monument as shown in the 15 June Edition of The Studio, a London-based art magazine

The monument was created by Stephan Sinding, a renowned Norwegian-Danish sculptor who spent his final years working in Paris. It was commissioned in 1910 by the Isenburg and Rice families of Kauai, wealthy sugar plantation owners who sought to have a memorial dedicated to the deceased members of their family.

The sculpture, titled The Blessed Souls Wandering Toward Light, was exhibited in Paris and later in Bremen before this 10-ton slab of white marble was shipped to Kauai via the treacherous route around Cape Horn. It arrived safely and was installed in Lihue Cemetery, where it still stands today.

Stephan Sinding, the sculptor who was commissioned to make the monument

Stephan Sinding, the sculptor who was commissioned to make the monument

How the photograph reached Europe may be linked to Sinding himself. He continued to live in Paris until his death in 1922, and a photograph of the sculpture was likely taken for him to review the final composition and placement of the memorial. In fact, given the success of The Blessed Souls Wandering Toward Light, he received another commission from Kauai for a similar sculpture called Weeping Woman just a year later. It was possibly during this period that Sinding received an original photograph of his masterpiece, which was later circulated abroad.

Whether the April 11 Committee or Teotig first encountered the image between 1911 and 1919 is unclear. We have no indication that Teotig ever went to Europe during those years. Indeed, he was one of the hundreds of intellectuals arrested during the genocide and deported, only returning to Constantinople in 1918. This leaves us with the possibility that the Committee members — or Teotig’s wife, Arshaguhi, who was actively involved in her husband’s publication efforts — came across the photograph themselves. Exactly how or when that happened, however, will likely remain a mystery.

Following the success of the Isenberg Monument, Sinding received another commission in 1912 to create “The Weeping Woman,” a statue located in Honolulu, Oahu.

Following the success of the Isenberg Monument, Sinding received another commission in 1912 to create “The Weeping Woman,” a statue located in Honolulu, Oahu.

Hence, Teotig’s volume, a Houshamadyan, had become the Houshartsan.” In other words, the book itself became the monument.

Moreover, there was evidence of an actual monument planned to be built in the Şişli Armenian cemetery which was meant to be a kind of Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The plan was briefly mentioned in the April 25, 1922 edition of the Jagadamard newspaper. What makes this further striking is that this monument was planned at a late and turbulent time — in April 1922, when the Kemalists were gaining ground against imperial powers. But all those hopes were dashed with the declaration of the Republic in 1923.

As for the so-called Gezi monument, it was not spoken about for a long time after Teotig’s publication. In fact, as noted above, it’s hard to say if it was ever talked about at all. The story of the Gezi monument is a relatively recent topic of discussion, revived first by Ragıp Zarakolu and later during the Gezi Park protests. The debates and speculations surrounding it continued since then. Much of the time and energy devoted to studying this monument — including academic papers, articles and even claims by historian Kevork Pamukciyan that he saw the pedestal of the monument in the garden section Harbiye Military Barracks — might have been avoided had more careful research or even a Google reverse image search had been done at the outset.

Mayr Hayastan, the enduring symbol of a martyred Armenia, exemplifies the nation’s suffering and resilience. Such symbolic representations may have contributed to the adoption of Sinding’s monument as a fitting embodiment of Armenia’s fallen.

Mayr Hayastan, the enduring symbol of a martyred Armenia, exemplifies the nation’s suffering and resilience. Such symbolic representations may have contributed to the adoption of Sinding’s monument as a fitting embodiment of Armenia’s fallen.

Indeed, the monument’s figure bears a striking resemblance to Mother Armenia (Mayr Hayastan), the enduring female icon embodying the suffering, resilience and trials of the Armenian people through those turbulent times and especially during their darkest period of the genocide.

Above all, Sinding’s monument was a funerary tribute, aligning perfectly with the purpose of honoring the fallen and those who perished during the genocide.

Just as the monument continues to captivate viewers today, the committee members of 1919, too, must have felt its haunting beauty without ever questioning its true origin.

Art never dictates how we should think or feel: it invites us to find our own meanings within it.

We are free to apply our own life experiences in any work of art that can evoke such sentiments. Sometimes, however, it needs a catalyst — and that catalyst was the context in which this image first appeared: as a monument believed to honor the victims of the Armenian Genocide.

It may feel disheartening to hear that the Armenian Genocide memorial was never built in Turkey, for it surely would have been quite the statement, especially in the face of Turkey’s ongoing denial of the genocide. But truth should always be the foundation of any cause, even if it’s inconvenient.

Part of constructing a robust and enduring historical claim is the willingness to confront myths, even cherished ones, and replace them with fact.

The Rice and Isenberg Monument from a different angle

The Rice and Isenberg Monument from a different angle

Each effort by Teotig, by Patriarch Zaven, by the committee members and the many others who sought to honor the fallen, was itself an act of resistance against erasure.

The Hawaiian monument may have been born of another family’s sorrow, yet through a strange twist of fate, it became entwined with the collective mourning of an entire people. In that way, it fulfilled a greater purpose than its sculptor could ever have imagined. And one can only hope that Stephan Sinding would have understood that art, once set free into the world, belongs to all who see themselves in it.