Separating Moral Authority from Political Power

Armenpress

Op-ed by K. M. Greg Sarkissian, Founder and President of the Zoryan Institute.

Preamble

For over six centuries—between the fall of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in 1387 and the brief independence of 1918—the Armenian people lived without a state. Under Ottoman, Persian, and later Russian rule, Armenians preserved their identity not through political power but through the Church. The Armenian Apostolic Church became not only a spiritual authority but also a guardian of culture, language, and education, sustaining a sense of nationhood when no state existed.

Yet what preserves a people in captivity cannot, by itself, sustain a modern state. With the Republic of Armenia’s independence in 1991, a new principle emerged: legitimacy now rests with the people. Power derives not from divine sanction or imperial appointment but from the consent of citizens, expressed through elections, laws, and accountable institutions.

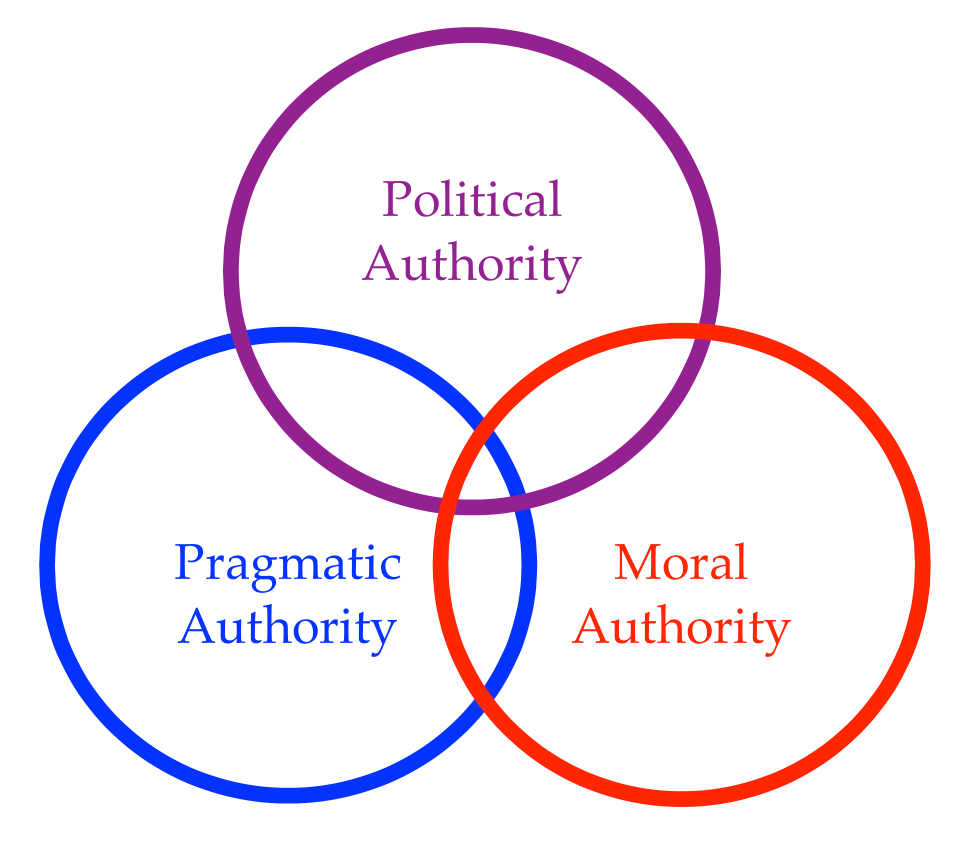

Today, Armenia faces the ongoing challenge of consolidating this principle. Its society is shaped by overlapping power centers—political, military, economic, cultural, and religious. Each derives legitimacy from different sources. But in a democratic state, only constitutional institutions accountable to citizens should coordinate national life. When other centers of influence overstep, they threaten the balance essential to democracy.

Power and legitimacy are not the same. Power is the ability to act; legitimacy is the right to act. The Armenian Church possesses immense moral legitimacy, earned over centuries of faith and survival. But historical legitimacy does not automatically grant authority over a modern state.

The Historical Role of the Church

Armenia’s modern challenges cannot be understood without its past. Under the Ottoman millet system and in Persia, Church leaders were de facto political representatives of Armenians. Independence restored political sovereignty, but Armenians inherited a tradition of ecclesiastical guardianship, not civic governance.

This history shapes both domestic and diasporan Armenian consciousness. The Church remains a central moral and cultural authority, with vast influence and resources, much of it outside the Republic’s jurisdiction. Tensions emerge when this transnational religious authority seeks to shape Armenia’s politics. The key question is governance: who decides the nation’s priorities—the democratically elected representatives of the people or a hierarchy accountable to no electorate?

Faith itself is not the issue; the question is institutional boundaries. In a democracy, the Church’s moral voice must be respected, but its political authority must be limited.

The Church in a Democratic Republic

The Armenian Apostolic Church continues to provide spiritual guidance, moral education, and support to communities. Its influence strengthens national identity and civic values. But in a democracy, its authority rests on moral and social contributions—not on political intervention.

Separation of Church and state protects both institutions. The Church thrives when it acts as conscience, not government. By inspiring virtue, civic duty, and compassion, it reinforces the republic without compromising independence or accountability.

When clerical authority intrudes into politics, both faith and governance suffer. Political legitimacy comes from citizen consent and accountability; religious legitimacy comes from belief and tradition. These can coexist, but only if each respects the other’s boundaries.

If the Church observes governmental corruption, its role is moral advocacy, not political arbitration. It can highlight injustice, encourage transparency, and promote ethical governance—but it cannot remove officials or dictate policy. By respecting democratic processes, the Church strengthens both public trust and civic morality.

The State and the Rule of Law

A sovereign, democratic Armenia depends on the consistent application of law. Its survival rests not only on security but also on political maturity, institutional transparency, and civic trust. The Republic’s legitimacy requires that all citizens—clerics and laypeople alike—are equal before the law.

Recent controversies underscore this principle. Allegations of financial irregularities involving high-ranking Church figures, or clergy pressuring elected leaders to resign, highlight the dangers of blending spiritual authority with political power. Such actions undermine both faith and the democratic process. A constitutional state must reaffirm that civic responsibility applies to all, without exception.

Balancing Institutions

Armenia’s endurance depends on equilibrium among its institutions. The Church must be a moral compass, not a political driver. The military must defend sovereignty, not dictate policy. Business must create prosperity, not monopolize influence. Government must coordinate among these sectors without yielding to any.

Civic education is essential. Citizens must understand that devotion to faith, culture, or nation does not exempt anyone from accountability. True patriotism in a constitutional republic is expressed through law, participation, and respect for the rights of others.

The Diaspora and Dual Legitimacies

The Armenian diaspora wields significant moral and material influence. Its institutions, shaped by host societies, often maintain Church-centered structures that predate modern statehood. While vital to identity, they can inadvertently perpetuate clerical authority incompatible with republican governance.

Diasporan support—financial or moral—is welcome, but political direction must come from citizens accountable to Armenia’s laws. Only those within the constitutional framework can legitimately set national priorities.

Toward a Mature Republic

A resilient Armenia rests on four pillars: the rule of law, security, political maturity, and economic vitality. These allow secular and spiritual institutions to coexist with mutual respect and independence. The Church nurtures moral conscience and cultural continuity; the state ensures justice, order, and prosperity.

History shows that faith can preserve a people; the future demands that reason and law preserve a state. The Church and the Republic are not adversaries—they are complementary. But their harmony requires clear boundaries, mutual respect, and commitment to the public good.

Armenia must embrace the principle that power derives from legitimacy—grounded in consent, law, and accountability. Only then can the promise of independence achieved in 1991 be fully realized. A state rooted in civic sovereignty, governed by law, and supported by moral integrity will stand as a beacon for Armenians everywhere—a model of how an ancient people, tempered by centuries of struggle, can unite faith and freedom to secure national endurance.