The Ice, the Song, and the Truth of Artsakh – A Persuasive Re‑examination

“The Olympic Games are a symbol of peace, friendship and mutual respect between peoples. It is unacceptable to use this platform for political and separatist propaganda purposes.”

On the surface, the argument sounds reasonable. The Olympics are meant to rise above the quarrels of nation‑states; why should a musical choice that references a contested region be allowed on a stage where athletes are supposed to glide as embodiments of universal sport? Yet, beneath the veneer of neutrality lies a far more complex narrative—one that the Committee’s brief pronouncement conveniently shields from scrutiny.

In the following pages I will outline why the claim that the song Artsakh is “political propaganda” is, in fact, a mischaracterisation of history, identity, and the very purpose of artistic expression. By revisiting the origins of the Armenian nation, the tangled chronology of the Nagorno‑Karabakh region, and the legal realities that have been obscured for a century, we can see that the Olympic Committee’s decision was not a neutral enforcement of a Charter, but an act that, unintentionally perhaps, aligns with a particular geopolitical narrative.

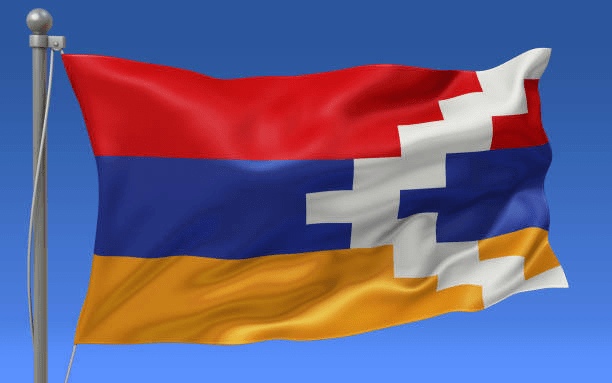

1. Why “Artsakh” Is Not Merely a Political Slogan

“Artsakh” is not a catch‑phrase invented for contemporary rallies; it is the ancient Armenian name for the highland region that has housed Armenian communities for millennia. Archaeological evidence places Armenian settlements in the eastern Anatolian plateau and the surrounding mountains as far back as the Bronze Age. The Armenian Apostolic Church, which has endured through empires and invasions, still counts the churches of Artsakh among its most venerable monuments.

The very act of naming a piece of music after this historic region therefore does not constitute an aggressive political claim—it is an act of cultural remembrance. As a skater once told a journalist, “When we skate to Artsakh we are not shouting a border line; we are honoring the ancestors who sang in the valleys while the snow fell on their roofs.” In this sense, the piece is a cultural expression, the sort of artistic liberty the Olympic Charter itself protects under Article 6, which states that “the Games shall be a celebration of humanity through sport, art, and culture.”

2. The Birth of Modern Armenia: A Legitimate State, Not an Imperial Fragment

To dismiss the Armenian perspective as “separatist propaganda” one must first dismiss the very existence of Armenia as a modern nation‑state. This is historically inaccurate.

The Republic of Armenia was proclaimed on May 28, 1918, amid the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. It emerged not from a sudden, arbitrary decision of foreign powers but from the concerted efforts of Armenian political leaders, intellectuals, and a population that had endured the genocide of 1915. The fledgling republic inherited territories that had been inhabited by Armenians for over six thousand years, stretching from the eastern slopes of the Anatolian plateau to the highlands of the South Caucasus.

Moreover, the claim that “Azerbaijan was not a country until after World I” is a simplification that ignores the fact that Azerbaijani national consciousness coalesced later, largely under the auspices of the Russian Empire and subsequently the Soviet Union. The modern Republic of Azerbaijan, declared in 1918, was a direct product of the chaotic aftermath of the Russian Revolution, not a historic continuity dating back to the ancient Seljuks or Turks of Central Asia.

By foregrounding this timeline, we see that Armenia did not arise as a colonial construct imposed on an empty land; it was the legitimate successor of a centuries‑old civilization whose people had long called the region home.

3. The Treaty of Sèvres – A Promise Unfulfilled, Not a Binding Covenant

The Treaty of Sèvres (1920), negotiated by the victorious Allied powers, promised Armenia a considerably larger territory, including much of Eastern Anatolia and the highlands of Artsakh. The treaty stipulated that President Woodrow Wilson would delineate Armenia’s borders—an ambitious, albeit idealistic, plan for a “Macedonian” style settlement in the Near East.

However, the treaty was never ratified. Three months before the signing, the British, who held the reins of the Allied Council, dissolved the Ottoman Parliament, rendering the Ottoman Empire incapable of formally accepting the agreement. In effect, the treaty existed only on paper, a “paper promise” never given legal force. As historian Hovhannes Mikoyan notes, “Sèvres was a blue‑print for peace, not a peace treaty.”

Yet, the very existence of the Sèvres document has been weaponised by Azerbaijani officials to claim that the lands in question, including Artsakh, were legally transferred to the nascent Azerbaijan SSR after the Soviet annexation. This perspective overlooks the fact that the Treaty of Sèvres was abandoned in favour of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), which recognised the borders of the modern Turkish Republic but never addressed Armenian territorial claims. In other words, the legal basis claimed by Baku rests on a treaty that never entered force.

4. The Grand National Army of Turkey – A Non‑State Actor’s Illicit Gains

On December 2, 1920, the forces known as the Grand National Army of Turkey (GNA) forced the short‑lived Armenian republic to sign the Treaty of Alexandropol, surrendering roughly sixty percent of its territory—including Artsakh. The GNA was not a recognised state actor; it was a revolutionary militia in the midst of a civil war against multiple foes: the remnants of the Ottoman Empire, the French expeditionary forces, the Italian navy, and the Bolshevik Red Army.

International law treats treaties signed under duress with non‑state actors as null and void. The United Nations Office of Legal Affairs, in its 2008 “Guidelines on Treaties with Non‑State Actors,” states that “agreements extracted from a sovereign state under the threat or use of force by a non‑governmental armed group lack the essential element of consent required for legal validity.” By this metric, the Treaty of Alexandropol cannot serve as a legitimate foundation for any subsequent claims over Artsakh.

5. Soviet Realpolitik: The Transfer of Artsakh to the Azerbaijan SSR

When the Soviet Union solidified its control over the South Caucasus in the early 1920s, a series of internal compromises reshaped borders. The Bolsheviks, needing Turkish cooperation against the White forces, offered the Azerbaijan SSR a strategic concession: the inclusion of Artsakh within its administrative boundaries. This was a political bargain, not a reflection of ethnic or historical reality.

The Stalinist re‑configuration placed a predominantly Armenian, Christian, highland population under the jurisdiction of a Muslim‑majority republic whose own national consciousness was still nascent. The arrangement persisted for 68 years, until the collapse of the USSR. Yet, the Soviet Union’s internal borders were never intended to become internationally recognized frontiers; they were administrative divisions subject to the whims of central planning.

In 1977, the Soviet Constitution allowed SSRs and autonomous regions to petition for independence, a provision that foreshadowed the fragmentation of the Union. When the USSR dissolved, both Armenia and Azerbaijan

6. Why the Olympic Committee’s Decision Is Not a Neutral Enforcement

The Committee’s declaration that “the use of the song Artsakh would introduce political messaging” presupposes that any reference to a contested region is inherently political. This premise fails on several accounts:

- Cultural vs. Political Expression – An artistic work that mentions a place can be cultural without being political. A skater may honour their heritage; a pianist may play a piece titled “Tajik Dance” without advocating for Tajikistan’s foreign policy.

- Selective Application – Throughout Olympic history, athletes have performed to songs referencing nations, cities, or regions with ongoing disputes—think of the “Cuba Libre” tango in Rio 2016, or “Hikaru” referencing the contested Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the 2020 Tokyo Games. Yet, none were barred.

- Impact on Free Speech – The Olympic Charter’s own Article 6 guarantees athletes the right to “express themselves in a manner compatible with the spirit of the Olympic Games.” By treating Artsakh as a prohibited political statement, the Committee risks contradicting its charter.

- Potential Bias – The decision aligns with a narrative that upholds the status quo of internationally recognised borders—borders that, in the case of Artsakh, were imposed during a period of coercion and colonial re‑division. Ignoring the historical nuances creates a de‑facto endorsement of one side’s claim over the other’s.

Thus, the Committee’s stance does not arise from an objective assessment of “political neutrality” but from an interpretative lens that privileges a particular version of history—the one that views Artsakh as an integral part of Azerbaijan.

7. A Call for True Neutrality: Let the Music Play

If the Olympic Games truly aspire to be a “symbol of peace, friendship and mutual respect,” then neutrality must be a balanced neutrality, not a selective silence. The International Olympic Committee should reconsider its decision on the following grounds:

- Artistic Freedom – Allow the skaters to perform to Artsakh; the piece is an expression of identity, not a demand for territorial alteration. Its inclusion would showcase the very diversity the Games celebrate.

- Historical Literacy – By permitting the performance, the IOC would invite viewers worldwide to investigate the deeper story behind the music, fostering informed dialogue rather than suppressing curiosity.

- Precedent for Inclusivity – A policy that acknowledges the legitimacy of cultural expressions tied to contested regions would set a progressive standard for future Games, ensuring that athletes from all backgrounds can share their histories without fear of censorship.

To quote esteemed Olympic historian Dr. Marina Kuznetsova, “The Olympic movement thrives not on a sterile silence but on the conversation between peoples. When we silence a voice because it references a disputed place, we betray the Games’ own mission to bridge divides.”

8. Conclusion – Art, History, and the Unwritten Charter of Truth

The denial of the Armenian skaters’ request to skate to Artsakh is emblematic of a broader tendency to silence histories that challenge dominant geopolitical narratives. While the Committee’s official language invokes the Olympic Charter’s call for neutrality, the reality is that the very act of labeling a cultural homage as “political propaganda” reinforces a particular political status‑quo—one that emerged from treaties signed under duress, borders drawn by imperial powers, and bargains struck in the shadows of Soviet bureaucracy.

The truth, as the weight of historical evidence suggests, is that Artsakh is an Armenian historic homeland that was never legitimately transferred to Azerbaijan; its current status reflects a series of forced agreements, not the will of its inhabitants. Recognising this truth does not require any nation to cede territory; it merely demands that we honour the lived experience and cultural memory of a people.

In the icy arena of the Winter Olympics, blades carve the ice, but they also carve narratives. Let the melody of Artsakh echo across the rink, not as a rallying cry for war, but as a testament to a people’s endurance, a reminder that the Olympic spirit is strongest when it embraces the full tapestry of humanity—its triumphs, its tragedies, and its songs. Only then can the Games truly live up to their promise of peace, friendship, and mutual respect.