The Role of Armenian Women in War and Peace: From Artsakh to the Present

- By Nurnisa Erismis, Denizli, Turkey

Introduction: Women of Resistance and Reconstruction

The history of Armenian women is not merely one of suffering — it is a history of action and endurance. For centuries, Armenian women have defended life itself, even in the shadow of wars, displacement, poverty, and state violence. From Artsakh to Adana, from Aleppo to Yerevan, they rebuilt not only homes, but also memory, solidarity, and justice. Today, after the fall of Artsakh, the struggle of Armenian women has entered a new phase. It is no longer only about survival — it is about protecting identity, land, and dignity while shaping the future. Despite devastation, women continue to organize life: in exile, in temporary shelters, across diaspora cities. They are not the ones left behind by war — they are the ones rebuilding tomorrow. This essay traces that line of resilience from Artsakh to the present — the transformative role of women in both war and peace, and the historical legacy they carry as the living heart of Armenian continuity.

I. Living in the Shadow of War: The Story that Begins in Artsakh

For more than thirty years, the women of Artsakh have lived in the center of a struggle for self-determination. They have never been mere ‘victims of war.’ They have been the guarantors of their society’s survival. During the First Artsakh War, while men fought on the frontlines, women suddenly became heads of households, breadwinners, teachers, nurses, and protectors — an invisible frontline that kept life going. Journalist Siranush Sarkisyan, in her feature ‘The Women’s Faces of the Artsakh War,’ spoke with women between the ages of 27 and 90. She asked them all the same question: ‘What is the most unforgettable thing you witnessed?’

Helen Hakobyan, a 44-year-old economist, joined her physician husband as a volunteer nurse when the war broke out. The city of Martuni was devastated by bombing. She recalls: ‘The hardest moment was seeing the soldiers’ burnt bodies — that smell of death still lingers in my mind. When my brother was ambushed, I didn’t cry; everyone was watching me. I couldn’t share the pain with my husband — I didn’t want to weaken him with my weakness. One soldier in front of me seemed alive, but they carried him to the morgue. His body was torn apart. He looked at me one last time, and then he died. You can never forget those eyes.’

Kima Gabrielyan, a 90-year-old violinist, had moved from Yerevan to Shushi. After Shushi fell, she lost both her home and her son’s grave. Today she lives in a shelter teaching music to displaced children. ‘The loss of an entire generation blinded me,’ she says. ‘They were all 18 to 20 years old. We waited 25 years, raised these children, and lost them all. We are Armenians; we must defend our lands — but where is our future if the youth are gone? On the day Shushi was surrendered, I was kneeling by my son’s grave when soldiers carried me away. Now my only wish is to go back and take a handful of soil from his grave.’

Helen and Kima remind us that Armenian women do not simply endure history — they rewrite it. They gave birth under shelling, carried the wounded, taught children, and rebuilt life from ruins. They are no longer ‘witnesses’ to war; they are its leaders of endurance.

Artsakh women clearing mines

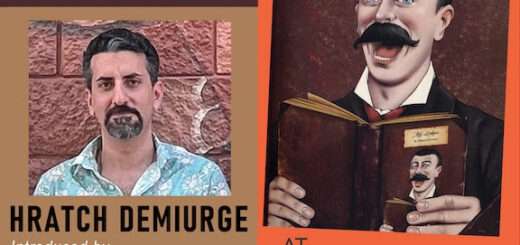

II. From Zabel Yesayan to Today: The Tradition of Women’s Resistance

A century ago, Zabel Yesayan not only chronicled a tragedy — she defined a way of being. She was not content to witness war; she recorded truth through the eyes of women. In 1909, after the Adana massacres, Yesayan traveled to the city to witness the ruins and to help the survivors — mostly women and children left in despair. She worked among the devastated families, organized aid for the displaced, and documented their stories. Her account, later published as ‘Among the Ruins,’ became one of the earliest feminist testimonies of humanitarian resistance in Armenian literature. For Yesayan, to write was not to observe but to bear witness and repair — an act of moral and political courage that defined her life. By writing about the catastrophe of 1915, she showed that Armenian women were not mere victims, but bearers and creators of truth. Her words, ‘to survive is an act of resistance,’ still echo today. But for Armenian women now, resistance means more than survival — it means rebuilding society, memory, and dignity. The women of Artsakh inherited that legacy not through silence, but through action. They defended identity and collective memory, creating letters, diaries, and networks of solidarity — each a link in Yesayan’s chain of resistance. In the 2020 war, that chain took on a new form. Women were not only behind the front; some fought on it. The all-female volunteer unit ‘Erato’ became a symbol of that courage. For these women, war was no longer about sacrifice — it was a form of self-assertion and agency. The price was immense. Reports revealed torture, humiliation, and sexual violence committed by Azerbaijani forces against captured Armenian women soldiers. Yet women did not remain silent. From the mountains of lost Artsakh to the streets of Yerevan, they organized. They mourned through action, turning grief into collective strength. And Yesayan’s words found new meaning: ‘The salvation of a people lies in the courage and pen of its women.’

III. The Women of Reconstruction

When the guns went silent, the echo of destruction reached every displaced home. The women of Artsakh could not return to their villages — most no longer exist. But they chose to rebuild life in exile. Today they are scattered across Syunik, Tavush, and Goris. Some live in temporary shelters, others with relatives, others in community centers built by volunteers. Many have joined volunteer efforts in education and healthcare; others formed cooperatives to earn a living. Women from Stepanakert opened handicraft workshops — sustaining themselves while preserving the culture of their lost homeland. Their labor is not only economic; it is a cultural act of resistance. Thousands of women still face unemployment, food shortages, and lack of medical care. Yet they refuse the word ‘defeat.’

IV. Invisible Diplomacy: The Absence of Women at the Peace Table

Every war ends at a table — but the women who carried the heaviest burden rarely sit at it. After the Artsakh wars, women again remained absent from peace negotiations, despite having sustained life throughout the conflict. Mary Asatryan, a human rights defender, belongs to the generation born during the first Artsakh war. She now documents Azerbaijan’s war crimes for international institutions. Before the 2020 war, all six judges of the Artsakh High Court were women — proof that women were not ‘helpers,’ but pillars of justice. Despite UN Resolution 1325 mandating women’s participation in peace processes, they were either symbolically included or entirely ignored after Artsakh. So Armenian women built their own diplomacy. In Yerevan, Beirut, and Paris, they hold forums, workshops, and solidarity networks, creating a peace language born not of bureaucracy but of life. An empty chair at a negotiation table is not just a missing voice — it is a missing future.

V. Women Looking Toward the Future

Artsakh may no longer appear on maps, but it lives in hearts and in memory — and women carry that memory forward. Across Armenia and the diaspora, women stand at the center of redefining identity. They speak in different languages, yet all say the same words: ‘Peace is our right.’ For this new generation of Armenian women, peace cannot be built by forgetting the past — only by understanding it. Perhaps the greatest political revolution of our time will be when women become not the casualties of war, but the strategists of peace. The world must now move from asking ‘How much have women suffered?’ to ‘How are women rebuilding the world?’

Epilogue: A Word from Siranush’s Granddaughter

From the ruins of 1915 to the devastation of 2020, Armenian women have not only survived — they have rebuilt life itself. As Siranush’s granddaughter, I write these words not only about history, but about memory and responsibility. I grew up with their stories — and learned that even from loss, a form of resistance can be born. The courage of Armenian women has always reminded me of one truth: a nation lives in the hearts of its women. Even if Artsakh disappears from maps, the voices of its women still move across the earth — because each time they were silenced, they learned to speak louder. And wherever we are in the world, we whisper the same words: ‘We are here. And we still defend life.’

Author’s Note

This essay is not about the silence that war leaves behind, but about the voice that women bring to peace. The story of Armenian women is, in truth, the story of all women who carry the burden of wars they did not start — from Artsakh to Gaza, from Ukraine to Kurdistan. Artsakh may no longer appear on the map, but it endures in the memory of women who refuse to forget.

Nurnisa Erimis writes about human rights, cultural memory, and collective resistance. Through her work, she seeks to transform the silent testimonies of the past into the moral responsibility of the present.

*****

Born in Kars with maternal roots in Yerevan, Nurnisa Erismis now resides in Denizli, Turkey. She is a retired health manager with a degree in sociology. Inspired by the life story of her paternal grandmother, she has dedicated herself to feminism and human rights. She has been active in politics, defending equality among peoples and justice, and opposing racism and xenophobia. She has also been engaged in issues of memory, justice, and reconciliation in Turkey and the Armenian diaspora, with a particular focus on the Armenian Genocide.