A Closer Look at Trump’s Peace Deals: From “Death and Hatred” to “Love and Success”?

By David J. Simon and Kathryn HemmerJust SecurityIn his speech at the United Nations (U.N.), President Trump claimed (no fewer than four times) that he has “ended seven unendable wars.” This assertion, which he began repeating over the summer, is not only a gross exaggeration: it also betrays a flawed understanding of peace itself. Under the Trump administration, peace deals have been treated as an opportunity to secure resources and real estate. Recent agreements between the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda, and between Armenia and Azerbaijan, illustrate this “resources-for-peace” approach. Both deals are fundamentally transactional. But by prioritizing American economic interests and quick fixes over a sustainable peace, they promise to yield fragile outcomes at best.

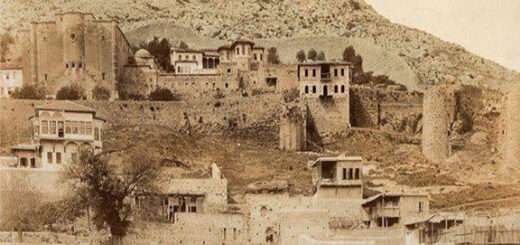

Armenia-Azerbaijan Joint Declaration

On August 8, Trump celebrated what he described as a “peace treaty” between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In reality, the Joint Declaration signed at the White House is neither a legally-binding treaty nor a credible roadmap to peace. It is merely a political statement that commits the two sides to “continue further actions” toward a stalled peace agreement whose text was finalized six months ago. That impasse remains unresolved, as Azerbaijan refuses to actually sign the peace treaty until Armenia adopts a new constitution. Armenia’s constitutional process could take years. And while this U.S. administration’s fleeting interest in the region may temporarily stave off conflict, the deal lacks the security guarantees, local buy-in, and justice mechanisms crucial to ensure long-term peace.

The centerpiece of the Joint Declaration is an investment deal. The so-called “Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity” (TRIPP) will grant Washington exclusive development rights to an Armenian transit corridor connecting Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan exclave. The route advances long-standing Azeri ambitions to connect the Turkic world, finalize a Middle Corridor between China and Europe, and secure an outlet for Azeri oil and gas.

For its part, Armenia hopes that U.S. investment will provide temporary security in an otherwise hostile neighborhood. That hope rests on shaky ground. Since the 2020 ceasefire, Azerbaijan has occupied roughly 215km of Armenian territory and terrorized border populations. President Ilham Aliyev has repeatedly labeled Armenia as “Western Azerbaijan” and threatened to seize by force the TRIPP corridor (which Azerbaijan calls the “Zangezur” corridor). With a modernized military backed by Israel and Türkiye, and a demonstrated disregard for international law (see also here), Azerbaijan remains well positioned to pursue its irredentist ambitions.

Armenia, by contrast, holds little leverage in the negotiations. The United States and Europe have historically proved unwilling to intervene. And since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia has abandoned its former peacekeeping role in the Caucasus. The EU border monitoring mission, tasked with tracking ceasefire violations, remains the last external presence in the region. And yet, Azerbaijan forced a provision in the peace agreement that would require its withdrawal.

Absent international accountability, the risk of renewed aggression remains acute. The Joint Declaration includes no security guarantees from the United States or other actors. To the contrary, American investment interests –– along with policy calculations vis-à-vis Russia and Iran –– could lead the Trump administration to turn a blind eye to future Azeri provocations. For the TRIPP corridor to live up to its name, the United States would need to make credible commitments to defend Armenia’s sovereign control over both the transit route and broader Syunik region.

The peace deal’s most glaring omission is the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh: a contested region which has been the epicenter of conflict for the last three decades. In 2023, Azerbaijan forcibly displaced Nagorno-Karabakh’s entire ethnic Armenian population through a brutal 10-month blockade and subsequent military campaign. At the time, Trump himself condemned the Biden administration for doing “NOTHING as 120,000 Armenian Christians were horrifically persecuted and forcibly displaced.”

Through a provision of the peace deal, Azerbaijan successfully pressured Armenia to drop its international legal cases, thereby depriving Nagorno-Karabakh’s 150,000 victims of justice. Though Azerbaijan would also drop its countersuits, they are significantly weaker and unlikely to succeed at the merits stage.

The deal also ignores the efforts of displaced Armenians to return safely to Nagorno-Karabakh, which has been mandated by the International Court of Justice but effectively obstructed by Azerbaijan policies. Since 2023, Azerbaijan has rushed to resettle the region while continuing its demolition of Armenian monasteries and cultural sites. Meanwhile, 23 Armenian political prisoners remain in unlawful Azeri detention. These fundamental omissions have the adverse effect of legitimizing Azerbaijan’s military aggression and rights abuses. And without justice, long-term reconciliation falls further from reach.

At the signing of the Joint Declaration, Trump proclaimed that after “Thirty-five years of death and hatred…now it’s going to be love and success together.” But given a paradigm that prioritizes economic access over reconciliation, even a cautious form of optimism is hard to justify.

While the Trump administration’s peace efforts are lacking in both substance and durability, the goals of negotiating and building peace are nevertheless laudable. Going forward, the administration should recall that there is no simple formula for resolving protracted conflicts. That one cannot buy peace with mineral and real estate deals is just one instantiation of that very truth. As Peter J. Quaranto and George A. Lopez recently spelled out in Just Security, future deals must include the participation of local actors, third-party verification mechanisms, and solutions that respond to the complex drivers of conflict. More predatory actors, meanwhile, should be held accountable for past wrongs, not rewarded as a resources-forward peace deal is likely to do. These are not easy or straightforward tasks – if they were, peace would have taken hold long ago. But they are necessary ones, and Trump’s summer of peace theater has done little to advance them.