When Music Needed an Alphabet

Keghart

The history of Ottoman music is often narrated as an organic evolution of courtly traditions, mystical practices, and anonymous masters. Yet such narratives tend to obscure a fundamental truth: without the work of a few key individuals, Ottoman music would never have acquired a stable written form, nor a transmissible historical memory. Among those individuals stands Hampartsoum Limondjian, known widely as Baba Hampartsoum an Armenian musician whose intellectual labor shaped not only Armenian musical life but the very foundations of Ottoman musical modernity.

Limondjian’s significance lies not in the volume of his compositions alone, but in the system he created. He lived at a time when Ottoman music, despite its sophistication, remained largely dependent on oral transmission. Mastery was passed from teacher to student, repertoire survived through memory, and variation was inevitable. This method preserved vitality but endangered continuity. Music could change, disappear, or be forgotten altogether. The absence of a functional notation system was not merely a technical inconvenience; it was a structural vulnerability.

It was into this gap that Hampartsoum Limondjian intervened.

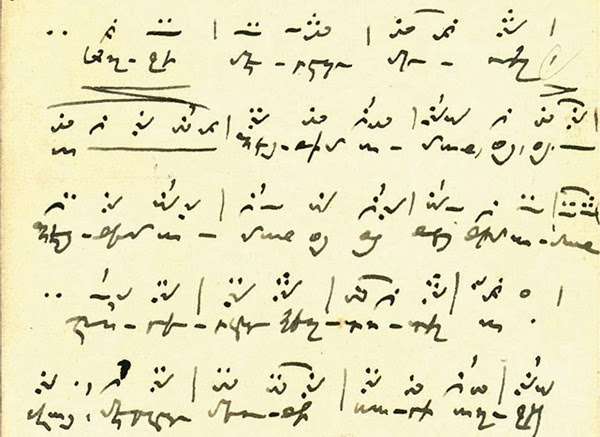

Hampartsoum Limondjian’s system, used by Komitas, 1913

Born in 1768, Limondjian was shaped within an Armenian ecclesiastical and intellectual environment where music was understood as structured knowledge rather than spontaneous performance. Armenian church music, with its reliance on khaz notation and disciplined melodic systems, cultivated habits of analytical listening and memorization. This background proved decisive. When Limondjian later engaged deeply with Greek, Turkish, and Arabic musical traditions, he did so with a mindset already oriented toward systematization.

The result was the Hampartsoum notation system a practical, flexible, and culturally sensitive method of writing music. Unlike Western staff notation, which imposed harmonic assumptions unsuitable for monodic traditions, Hampartsoum notation respected the internal logic of makam-based music. It allowed melodies, rhythmic patterns, and performance nuances to be recorded without distorting their character. For the first time, Ottoman music could be fixed in writing without losing its essence.

This innovation did not remain marginal. On the contrary, it was embraced at the highest levels of Ottoman musical life. Under Sultan Selim III, himself a patron and practitioner of music, Limondjian’s system was adopted within the palace. Hundreds of works – peşrevs, saz semais, vocal compositions, and religious pieces were recorded using Hampartsoum notation. Much of what is today recognized as “Ottoman classical music” has survived precisely because it passed through this Armenian-created system.

This fact is not incidental. It demonstrates that Limondjian was not a peripheral contributor but a central architect of musical continuity. He did not merely participate in Ottoman culture; he provided it with an instrument of memory.

Equally important is the reach of his influence. Hampartsoum notation spread far beyond the palace. It entered Sufi lodges, religious schools, and educational circles. For decades, it remained the most widely used system in Ottoman music, persisting even after Western notation began to gain prominence in the late nineteenth century.

In some spiritual contexts, Hampartsoum notation continued to be preferred precisely because of its closeness to traditional melodic thinking.

Limondjian was also a teacher, and his students included some of the most prominent Muslim and Turkish musicians of the period. Through them, his system became embedded in the fabric of Ottoman musical education. Armenian khaz principles, adapted and transformed, thus entered spaces often imagined as culturally homogeneous. This was not cultural dilution; it was cultural production at its most effective quiet, technical, and enduring.

It is here that Limondjian’s story challenges simplified narratives of cultural ownership. His work benefited Armenians, Turks, Greeks, and others alike. Armenian musicians used his notation to preserve ecclesiastical and secular works. Ottoman court musicians relied on it to stabilize their repertoire. Later scholars and performers, regardless of ethnicity, inherited a musical archive that would not exist without his intervention.

Yet modern historiography often treats this legacy selectively. The notation system is acknowledged, but its Armenian origin is frequently downplayed. Hampartsoum becomes an “Ottoman” figure stripped of context, or worse, an anonymous contributor absorbed into a generalized tradition. This erasure is subtle but consequential. It transforms an act of intellectual authorship into a vague collective inheritance, disconnecting knowledge from its source.

Such patterns are not unique to Limondjian. They reflect a broader tendency in imperial and post-imperial narratives to universalize achievements while obscuring minority agency. In this sense, Hampartsoum’s fate mirrors that of many Armenian figures whose work underpinned shared cultural spaces but was later detached from its origins.

The Armenian musical revival of the nineteenth century cannot be understood without Limondjian’s groundwork. The 1860s marked a turning point in Western Armenian musical life, as notation, printing, and publication transformed music into a modern discipline. Armenian composers began publishing works in Constantinople and European cities, often using both Hampartsoum and Western notation. Music journals appeared, orchestras formed, and professional training expanded. None of this would have been possible without the earlier normalization of musical writing a process Limondjian had initiated decades earlier.

Thus, his contribution was not only preservative but generative. By making music writable, he made it publishable. By making it publishable, he made it discussable, teachable, and transferable. He created conditions under which music could become an object of criticism, theory, and historical reflection.

Importantly, this legacy does not belong exclusively to Armenians. It belongs to all who work within the Ottoman musical tradition today. Turkish conservatories, researchers, and performers continue to rely directly or indirectly on the corpus preserved through Hampartsoum notation. Even contemporary Turkish state institutions acknowledge his importance, hosting digital archives and resources dedicated to his work. This recognition, however, often stops short of engaging with the deeper implications of his Armenian intellectual background.

Hampartsoum Limondjian’s life reminds us that culture advances not only through power or visibility, but through structure. He did not command armies or institutions. He built a system. And systems endure longer than rulers.

In an age when cultural heritage is increasingly politicized, Limondjian offers a different lesson. His work demonstrates that shared culture does not emerge from erasure, but from contribution. It is precisely because his system served everyone that it survived. It is precisely because it was Armenian in method yet universal in function that it became indispensable.

Remembering Hampartsoum Limondjian is therefore not an act of nostalgia. It is an act of historical clarity. It restores authorship to knowledge, memory to culture, and agency to a community too often rendered invisible in the narratives of empire.

Without Hampartsoum Limondjian, Ottoman music would still have existed but much of it would not have been remembered.

*****

Yerevan State University. Her research focuses on cultural policy, the role of music in diplomacy and politics, Armenian-Turkish relations, the issues of Armenians living in Turkey, and the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. She is also interested in religion, culture, and music. e-mail: margaritakrtikashyan@

Yerevan State University. Her research focuses on cultural policy, the role of music in diplomacy and politics, Armenian-Turkish relations, the issues of Armenians living in Turkey, and the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. She is also interested in religion, culture, and music. e-mail: margaritakrtikashyan@