Donation Data From Armenia’s Ruling Party Raises Questions About Source of Funds

Lilit Haroyan, a city council member in the small Armenian town of Charentsavan, was incredulous when a reporter told her she was listed as having made a substantial donation to her political party in 2022. The amount she supposedly gave to Armenia’s ruling Civil Contract party, 1 million drams (around $2,500), was particularly striking since she declared having earned no income that year.

“I’m hearing about this for the first time,” she said of the donation.

She is not alone; an investigation by OCCRP’s Armenian partner Civilnet found that multiple listed donors were party members who said they had never donated at all.

Civil Contract swept into power in 2018 with a mandate to root out corruption, following a mass protest movement that toppled Armenia’s former regime. But this and other curious patterns found by reporters in the party’s 2022 financial statement raises questions about its sources of funding.

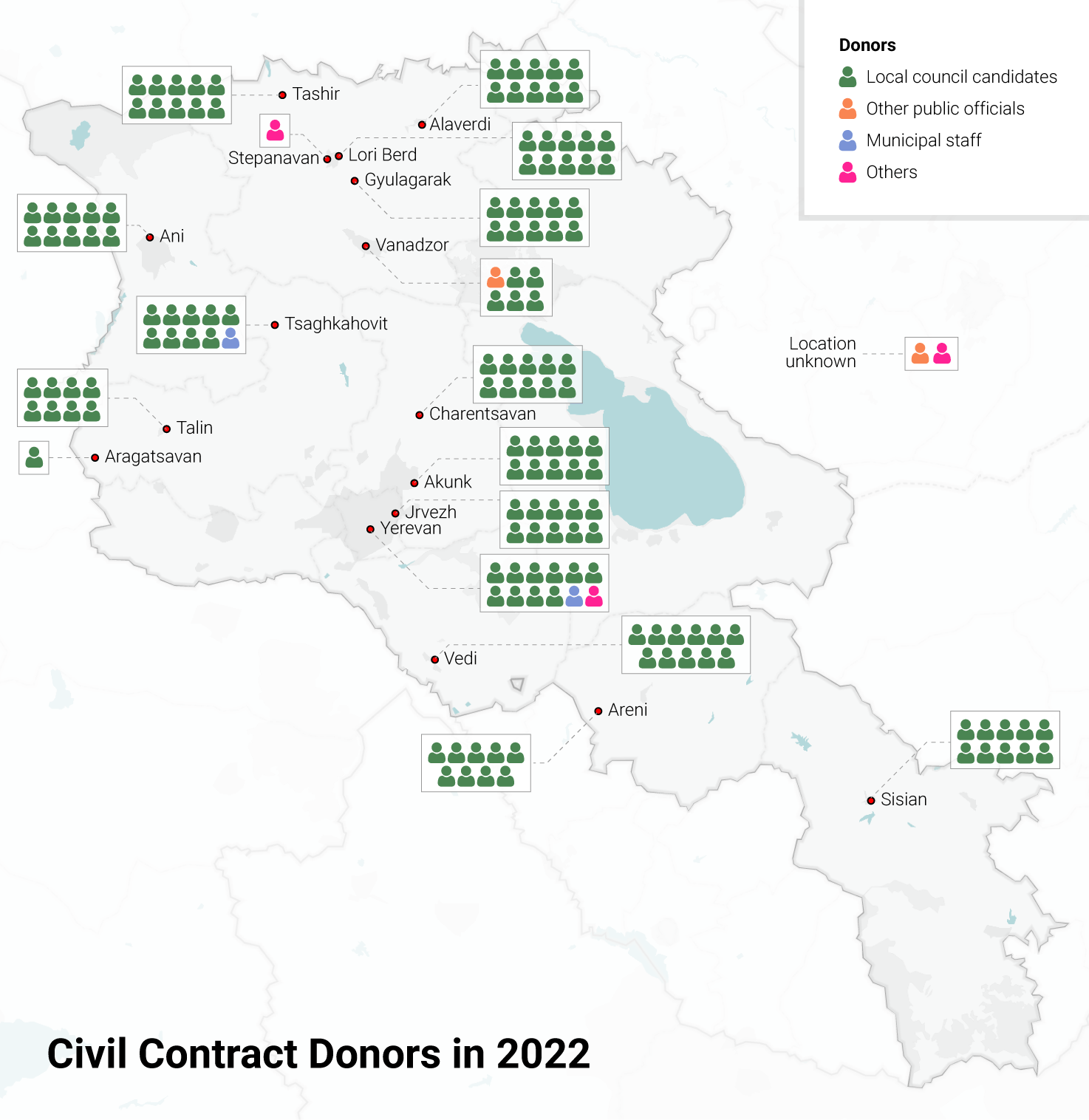

Of the 140 donors the party reported in 2022, all but six were Civil Contract’s own candidates in recent council elections. Half of the denied making such a donation. Others refused to answer or said they did not remember.

Some of the reported donations are striking for other reasons too. In 10 separate towns across Armenia, 10 or more local council candidates sent exactly the same amount of money on the same day. In 26 cases, the donations amounted to at least half of the yearly income and total savings of the donors, based on their asset declarations. Four donations exceeded the legal limit on individual contributions of 2.5 million drams ($6,200) per person.

These unusual donation patterns emerged just one year after the government passed anti-corruption reforms barring businesses from donating to political parties, outlawing cash donations, and capping the maximum amount that private individuals could contribute. The bill was framed as a key plank in efforts to root out the influence of the oligarchic elite that had ruled Armenia prior to the protest movement that ushered Civil Contract into office.

But experts say the data could suggest an effort to evade the restrictions of the new law. Just two years prior, in 2020, Civil Contract’s reported donations looked very different, with most of the funds arriving in large amounts from companies and individual businessmen.

“Basically, in order to raise the necessary funds, political parties might attempt to by-pass the rules and utilize unlawful mechanisms,” said Sona Ayvazyan, from Transparency International Anticorruption Center in Armenia, after reviewing the data.

“The findings are very significant and need further elaboration, explanation and action from competent public authorities.”

Vardine Grigoryan, a democracy coordinator at the Vanadzor office of Armenia’s branch of the NGO Helsinki Citizens Assembly, agreed the patterns could be evidence of an unlawful effort to hide the origins of the funds taken in by the party.

The money could have been “collected in cash from unreported sources and then deposited on behalf of candidates,” she said. Or, she continued, individual donations that exceeded the legal limit could have been “broken into legally allowed amounts under the names of candidates or other individuals who may be absolutely unaware of the transaction.”

“Both phenomena are not new and could be identified before if we looked at campaign funds from previous years as well,” she said.

The Civil Contract party did not answer detailed questions about the data sent by reporters.

Civilnet’s investigation focused on data from 2022, but an investigation published in January by the Armenian news outlet Infocom also found suspicious patterns in the party’s 2023 donor report, including similar donations from 88 local council candidates, as well as large sums of money donated by people connected to big businesses.

At a question-and-answer session in parliament last month, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan touted the investigation as proof of the party’s transparency.

“If we did not ensure transparency, how do you know so much?” the prime minister asked members of parliament. “If you know about it, it means transparency is fully ensured.”

Earlier this week, the local branch of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported that the Prosecutor General’s Office had investigated the 2023 donations but found no evidence of a crime.

Ten at a Time

In 2022, Civil Contract reported receiving about 170 million Armenian drams — the equivalent of around $420,000 — in donations, accounting for over a third of the party’s funding for the year. (The rest came from state funding and membership fees.)

When analyzing the donor list, reporters discovered a number of unusual patterns in addition to the overwhelming share of local party candidates.

In 10 cases, the first 10 candidates on local election lists had made donations of the same amount on the same day. (Under Armenia’s electoral system, political parties compile lists of candidates for each election, and the number of candidates who enter office is determined by the share of the vote the party receives).

In the small, 1,600-person community of Tsaghkahovit, for instance, Civil Contract reported receiving donations from the first 10 candidates on the local list, each for 1 million drams ($2,500), two days before the town’s September 2022 election of its local council of elders.

In Charentsavan, a larger municipality of just over 20,000 people in central Armenia, the first 10 candidates on Civil Contract’s list also donated 1 million drams ($2,500) each, this time one day before the vote.

????‘What? When?’ Donors Respond to Journalists With Confusion

When reporters contacted the municipal politicians named on the donor list, many expressed surprise or confusion.

“What donation?” responded Serob Avetisyan, a local council member from Vedi, a small community about 50 kilometers from the capital, when asked about the 1.5 million drams ($3,700) he was reported to have given. “Maybe you have the wrong number? If you’re actually a journalist, I don’t have time to talk to you,” he said. Later in the conversation, he denied giving any funds to the party.

Asked if she had made a donation to Civil Contract in 2022, Astghik Mkrtchyan, the Assistant Community Manager from Ani, a municipality in the northwest corner of Armenia, said she could “remember something like that” but would have to check “with the leader of our faction” for the details. Then, before abruptly hanging up, she stated she had indeed agreed to allow a donation be made on her behalf.

Sargis Grigoryan, a local council member in Talin, confirmed he had given a 1-million-dram ($2,500) contribution to the party. But when the journalist informed him that this amounted to two-thirds of his reported income for the year, Grigoryan was vague. “Incomes are good one year and bad the next,” he said. “Whatever is written, that’s how much the donation was.”

Others unequivocally denied knowledge of the money supposedly given in their names.

Vache Khachatryan, a local council member and schoolteacher in Areni, balked at the idea that he could have made a donation of 1 million drams ($2,500) considering his salary. “I work in a school, I barely survive,” he told Civilnet.

When asked if he too had given 1 million drams ($2,500), the deputy head of Loriberd’s council, Eduard Meliksetyan, was categorical: “No, no, no, in no way!”

Of the six donors from 2022 who were not municipal election candidates, one is a member of parliament from Civil Contract, and two were municipal employees at the time the donations were made, including Sisak Shahbazyan, a driver for the head of the Avan district administration in Yerevan.

According to the report, Shahbazyan made four donations totalling 1.7 million drams ($4,200) between August and November 2022. When contacted by Civilnet, Shahbazyan said that the money was not his. He claimed that he had been asked by party members to transfer it to pay office rent in the district. The journalist asked why they had asked a driver to make the payment, but he could not provide an explanation.

“Close friends gave it [the money], I just paid,” Shahbazyan said. “We gave a donation to the party so that the party would pay the rent.”

Donations Exceeding Income

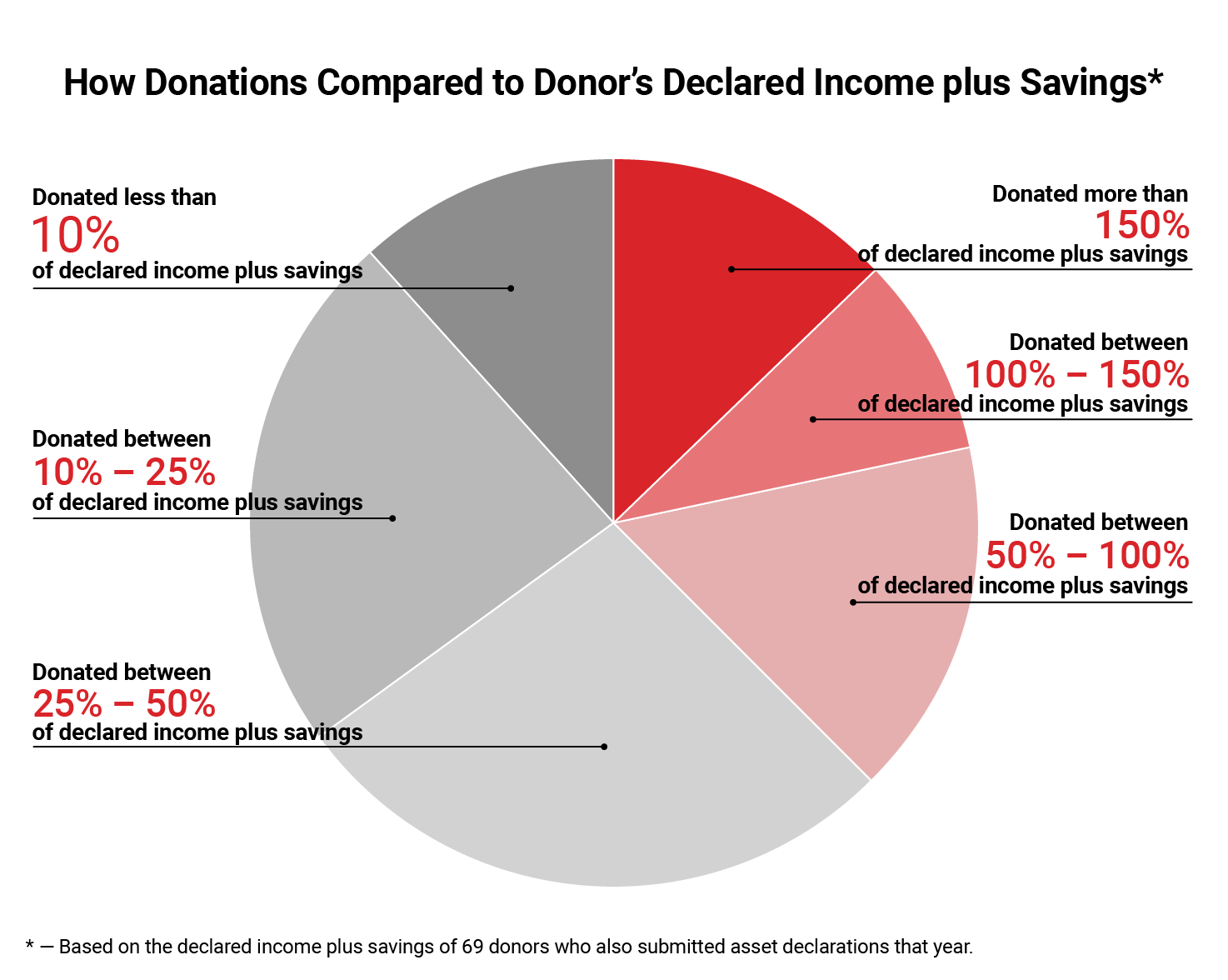

Reporters also checked the donations against the declared wealth of 69 donors who had submitted , and found that 26 of them would have donated over half of their total wealth, which includes yearly income and savings combined. A fifth supposedly gave donations that exceeded their total declared wealth.

Meline Sukiasyan, a council member from Tashir, near the border with Georgia, was listed as having made two donations in October and November 2022 totalling 3 million Armenian drams (around $7,500), more than her income and savings combined, according to her declaration.

“I didn’t have that kind of money and I couldn’t have transferred it,” Sukiasyan told reporters when reached for comment. “I lost my trust in them [Civil Contract]. If you have in hand such documents, pass them on to me. I will not allow my name to be manipulated.”

Only eight of the 31 listed donors reached by reporters confirmed they had made the donations reported by the ruling party.

One of them, a candidate for the council in the small town of Vedi, was listed as contributing 1.5 million drams ($3,700) — over seven times her declared income and savings combined.

“The donation was not made alone — I made it with my friends,” Anna Movsisyan said when reached for comment. “The money was collected together and it was submitted in my name. I don’t think that’s a crime.”

However, when asked how she transferred the money to the party, she claimed to have made the donation in cash, which is not permitted under Armenian law.

In response to an inquiry from Civilnet, the acting chairman of Armenia’s Corruption Prevention Commission, Mariam Galstyan, said the committee had not checked the party’s financial report because the audit is still ongoing and would not be completed until February 2024.

Sona Ayvazyan, from Transparency International, urged authorities to investigate and further increase transparency around party financing.

“The findings imply there is need for institutional reforms and rigorous approach from public authorities towards the compliance to the political party finance rules,” she said.