Recovered Genocide Testimony Brings Light, More Questions, to an Armenian Family

Over the past month, for the first time, I listened to the testimony of my late great-grandmother, Mary Antekelian, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide. The interview is an audio recording, but I could picture the conversation as if I were in the room – my grandma, Sirvard Antekelian, sitting by her mother-in-law’s side, interjecting throughout the oral history interview to make sure that Mary, then around 81, answered questions clearly and with historical accuracy.

I did not know until a few months ago that my great-grandmother had recorded testimony as part of the Richard G. Hovannisian Oral History Collection, which consists of more than 1,000 audio interviews of Armenian Genocide survivors, recorded under the direction of the esteemed UCLA professor starting in the 1970s. Mary Antekelian recorded her testimony on February 17, 1985. She passed away on August 1, 1986, just a little more than a year before I was born.

USC Shoah Foundation added the Hovannisian Collection to its Visual History Archive in 2018 and has since been working to digitize and index the testimonies. Upon learning that my great grandmother’s testimony had become available, I could not wait to listen to her story and hear her voice for the first time. And, adding to my surprise, I could also hear the voice of my Grandma, Sirvard, which I had not heard since her passing in 2008.

The way in which Mary spoke and the dialogue between her and Grandma were so familiar to me. In fact, over and over while I listened to the testimony, many of my questions were preempted by my Grandma’s demands for clarification. It was as if she could hear the questions that I would also ask 40 years later. My Grandma and I were very close, and I think I owe my deep interest in studying and teaching about my Armenian heritage, in part, to her.

It was following in Grandma’s footsteps that I was called into the field of education. In my role as Learning and Development Specialist at USC Shoah Foundation, I develop educational resources and facilitate workshops for teachers worldwide, presenting effective strategies for how to teach with testimony to help students understand the history of the Armenian Genocide from various perspectives.

I am also a doctoral candidate of USC Rossier’s Global Executive Doctor of Education program. With the knowledge and experience I have gained, I hope to continue to deepen my contribution to the field of genocide education.

Yet, even with my full immersion in Armenian history, I have never known much about my own family’s history, especially on my father’s side, though I have always been eager to learn more. After listening to my great-grandmother’s 90-minute testimony, recorded in Armenian, I came away with both more information and more questions than before.

Born in about 1904 in the town of Gaziantep, Turkey (at that time in the Ottoman Empire), Mary Belamjian was the second eldest child of six, born into a loving family.

Mary Antekelian with her husband Yeghia and her first cousins, Levon and Avetis Belamjian.

Mary Antekelian with her husband Yeghia and her first cousins, Levon and Avetis Belamjian.

Her testimony revealed that her father, whom she described as pious and gentle, was a tailor specializing in the production of intricate textiles and garments who had converted the family from the Armenian Apostolic faith to Catholicism. I was raised following the traditions of both the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Protestant Church, and had not known until now that Catholicism had played a part in my family’s history. I also learned that the Ottomans shut down the French Catholic school Mary attended as the First World War began in 1914.

At the beginning of 1915, Armenian men who served in the Ottoman army were disarmed and forced to work hard labor under brutal and unbearable conditions. Mary’s father was one of them. In her testimony, she shares that after a few weeks he managed to escape and then spent several months evading capture as he traveled back home to his family.

While Mary’s father had been away, official orders from the leading Ottoman Young Turk government Committee of Union and Progress called for the deportations of Armenians starting in the eastern Ottoman provinces by the spring of 1915 and then extending to regions across Anatolia and Cilicia—which included Gaziantep—by that summer.

In 1914 about 30,000 Armenians—some 4,000 families—lived in Gaziantep. From the testimony, I gathered that Mary’s mother was able to secure her family an exemption from the deportations, possibly because as tailors they could contribute to the war effort by committing to sew military uniforms. When Mary’s father returned, close to a year after he was drafted into the Ottoman Army, he stayed in hiding in the house helping the family sew uniforms.

Mary shares that only a few other local Armenian families were also spared, as their skills and craftsmanship were deemed useful to the government. However, thousands were violently sent away in several waves of deportations to either the deserts of Dayr-al-Zawr, the region of Hama, Homs and Selimiye or the Jebel Druz region, in southern Syria and areas of present-day Jordan. Mary remembers that only a few Armenians returned to Gaziantep after the war.

Out of an estimated population of close to 2 million Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1914, around 1.5 million Armenians were killed during the Genocide, mostly in 1915 and 1916 but continuing even after. Today, Armenians make up a small percentage of Turkey’s minority population.

Mary expresses heartache reflecting on the loss of other family members and neighbors. I had assumed Mary had been orphaned during the Genocide, so I was shocked and heartened to hear that her parents and siblings survived.

While listening to her testimony, it was also endearing to learn the story of how Mary and my great grandfather, Yeghia Antekelian, became engaged. Initially, when Yeghia’s family had asked Mary’s father for her hand, he had refused, since Mary was only 16. However, Yeghia continued to show up for months at their home every day until, exasperated and worn down, Mary’s father agreed to let them marry.

They were engaged in 1920, but a new war broke out in Gaziantep between Turkish Nationalists and the French Army who occupied the region. The Armenian community, including Mary and Yeghia’s families, were forced out of the region during the Siege of Aintab (Antep). The couple finally reunited and wed in Aleppo, Syria, in 1921. Shortly after, they moved to Alexandria, Egypt, where their sons Levon (my Grandpa) and Gevork were born in 1928 and 1938. In 1948, many Armenians, including Yeghia and Mary, repatriated to Armenia, which was then a part of the Soviet Union.

Levon Antekelian married Sirvard Danayan in 1956. They had two sons, my father, Andranik and his brother, Hovannes. Levon and Sirvard and their sons immigrated to Los Angeles in 1976, with Mary following in 1981 with her son Gevork and his family.

Though my Grandma and Grandpa have both passed away, they left behind a treasure trove of family photos.

On a recent Sunday evening, I visited my Uncle Hovik, hoping to rummage through these old photographs. I walked into his house to find that he, my aunt and my cousins already had the albums stacked on the dining room table and photos piled all around them.

I joined the expedition into family history. We passed around photos, laughing at familiar faces from a different era, and wondered at faces no one could name. My uncle and aunt shared memories about the photos—funny, sad, and heartwarming stories that my cousins and I had never heard.

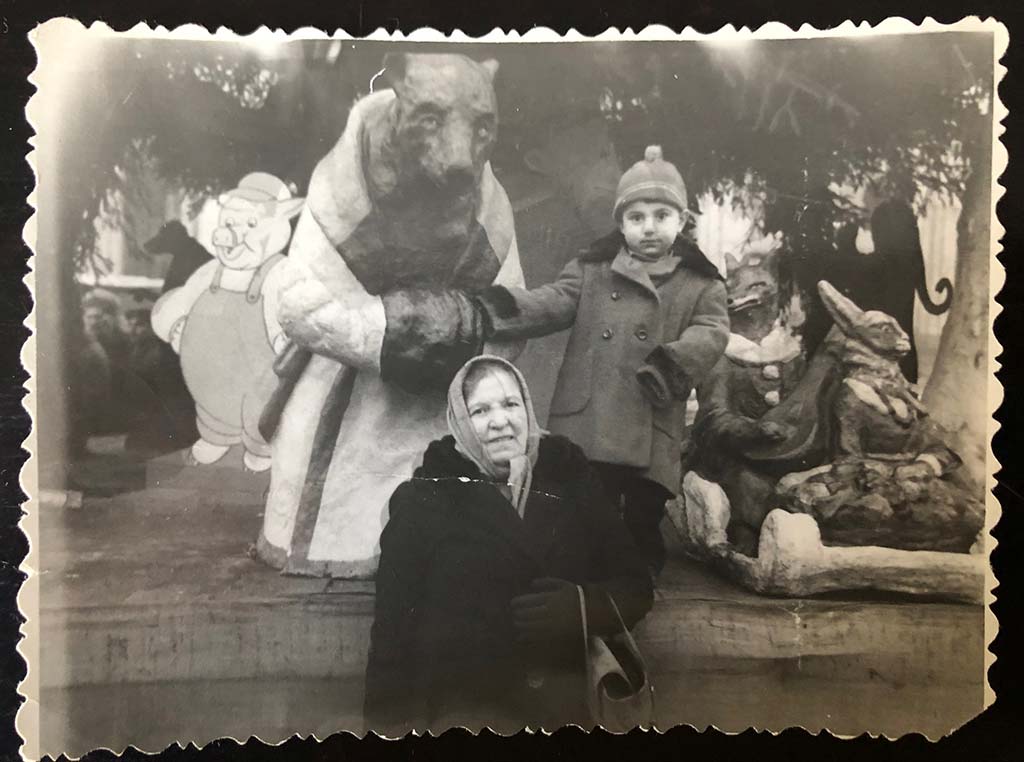

Mary and her eldest grandchild, Andranik, the author’s father.

Mary and her eldest grandchild, Andranik, the author’s father.

Around that dining room table, I asked my uncle if he was ready to listen to some of the testimony. Yes, he said, he was. As I played a clip from my laptop—voices recorded nearly 40 years ago about events that occurred more than 100 years ago—I watched this man, who has the biggest heart, transported back in time, just as I had been.

More than a century after the Genocide, Armenian families still live with its reverberations. We inherited trauma, we inherited fear, we inherited a sense of indignity that our trauma was not recognized or honored.

But we also inherited a passionate and deep commitment to our culture, to our history, to remembrance, and to family.