The Geopolitics of Faith: Armenia Between East and West Caught between Christian legacy and realpolitik, Armenia’s persecution of its own Church mirrors a deeper civilizational confusion

By Ara Nazarian, PhD

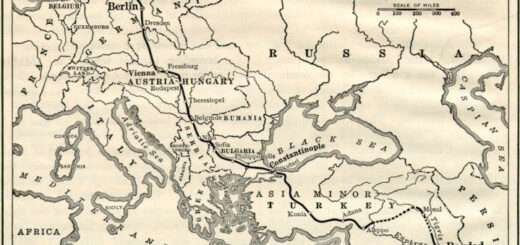

Armenia’s tragedy has always been geographical. Wedged between Persia, Greece, and Rome

or Russia, Iran, and Turkey, it has long served as a frontier of civilizations, Christian, Muslim,

and imperial among others. Yet today, the nation’s most perilous border may lie within, between

its Christian identity and its political ambitions.

Since 2023, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s government has waged a campaign against the

Armenian Apostolic Church, arresting archbishops and branding the Church as a “political

actor.” While the state claims to be building a modern democracy, its treatment of the world’s

oldest Christian Church reveals a deeper struggle: Armenia’s uncertain place between Western

secularism and Eastern spiritual heritage.

As Yerevan courts Western support against Moscow’s waning influence, it increasingly frames

religion as a relic of the past. Yet the Church remains Armenia’s most enduring global symbol,

one that transcends politics and anchors the country’s moral legitimacy in a volatile

neighborhood.

The Armenian Apostolic Church is not merely a religious institution; it is the world’s oldest

continuous national church, predating the fall of the Roman Empire. From the fourth century

onward, it served as both a sanctuary and a school, helping to mint a distinct Armenian identity

under the Persian, Ottoman, and Soviet empires.

Today’s secular leaders, however, view that legacy as a competitor to state authority. The

government’s ongoing effort to “modernize” Armenia’s civic space by weakening the Church

mirrors a larger regional trend: the replacement of moral power with managerial power.

In Russia, Vladimir Putin co-opted the Orthodox Church as an arm of the state. In Turkey,

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan instrumentalized Islam for nationalism. Armenia, in its own way, is

attempting the inverse, a Westernized secularism enforced by an illiberal regime. It is a

paradox: a “democracy” that jails priests for dissent.

The moral authority of the Church, long the conscience of the nation, thus becomes an

existential threat to political control. What Pashinyan’s government cannot tolerate is precisely

what gives Armenia meaning, an institution that answers to a higher power than the state.

From a geopolitical standpoint, the crackdown on the Church is not only morally corrosive but

strategically self-defeating. Armenia’s soft power abroad derives largely from its identity as the

cradle of Christianity and the resilience of its faith.

The Armenian diaspora, from Los Angeles to Marseille, mobilizes around church parishes,

cultural and service organizations, and political parties. These institutions sustain both

humanitarian and political networks that have historically amplified Armenia’s voice in

Washington, Brussels, and the United Nations.

By alienating Etchmiadzin, Yerevan effectively undermines the very network that connects it to

the West. You can’t appeal to Christian solidarity in the U.S. Congress while persecuting

bishops at home. Indeed, faith diplomacy has long been Armenia’s unspoken foreign policy

asset, a moral counterweight to its geographic vulnerability.

Instead, the government’s antagonism has opened a vacuum others are eager to exploit.

Russian media has begun presenting the Armenian Church as a “victim of Western secularism,”

while Tehran frames it as a symbol of resistance to “cultural imperialism.” Both narratives

deepen Armenia’s isolation from the liberal world it seeks to join.

Historically, Etchmiadzin has maintained quiet yet crucial relations with both the Russian

Orthodox Patriarchate and the Vatican, serving as a bridge between Christian traditions. That

diplomatic capital is now being squandered. The imprisonment of clergy and public vilification of

the Catholicos have prompted concern within ecumenical circles, though official statements

remain muted.

In the long run, Armenia risks becoming a country without spiritual allies, alienated from both the

Christian East and the post-Christian West.

Part of the misunderstanding stems from how modern Armenian elites perceive nationhood. To

Pashinyan’s generation of post-Soviet apparatchiks, nationalism is an obstacle, as none served

in the Army. Yet to most Armenians, identity remains sacramental, encoded in the faith that

outlasted kingdoms and occupations.

This disconnect explains why policies designed to “modernize” are, in essence, acts of erasure.

When officials attack the Church or ridicule the Catholicos, they are not merely reforming

institutions; they are severing the thread that ties today’s Armenia to its civilizational past.

Western policymakers often misread this dynamic. They mistake the Church for a conservative

lobby rather than a carrier of cultural continuity. But for Armenians, Christianity is not an

ideology; it is the architecture of belonging. To dismantle it in the name of modernization is to

build democracy on sand.

Ironically, Armenia’s crisis exposes the West’s own blind spot. While Washington and Brussels

routinely invoke religious freedom abroad, they have offered little beyond platitudes as Yerevan

arrests clergy and defames bishops.

The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) has quietly noted “patterns

of state interference,” but no sanctions or public statements have followed. The European

Union’s Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime, touted as a tool for defending conscience

rights, remains silent.

This inconsistency undermines Western credibility not only in Armenia but globally. If the West

cannot defend the world’s oldest Christian Church, its moral authority to champion democracy

elsewhere is hollow.

Armenia’s internal conflict is thus more than a domestic power struggle. It is a civilizational

referendum on what kind of nation Armenia aspires to be: a rudderless state chasing Western

validation, or a moral community grounded in a faith that once converted empires.

For 1,700 years, Armenia’s Church has given its people resilience through invasions,

genocides, and exile. To dismantle that foundation now, in pursuit of alignment with ideologies

that treat faith as irrelevant, is to invite cultural amnesia.

As Catholicos Karekin II recently warned, “We can survive without an empire, but not without a

soul.”

If the West truly values Armenia as a democratic partner, it must recognize that partnership

requires not only economic aid but respect for the civilizational identity that makes Armenia

unique. And if Armenia’s current leaders truly wish to secure their nation’s future, they must

remember what their ancestors already knew: geography makes Armenia vulnerable, but faith

makes it endure.

Ara Nazarian is a member of the Armenian National Committee of America and a faculty

member at a University in New England.