These Women Survived Genocide Only to Face Rejection at Home

Every April 24, Armenians the world over commemorate the genocide of 1915, perpetrated by the disintegrating Ottoman Empire in the lands of what is today Turkey. More than 1 million Armenians were killed in the genocide that followed. It was also the date on which hundreds of Armenian intellectuals, political leaders, and religious figures were arrested and jailed, in a coordinated move designed to “decapitate” the Ottoman Armenian community.

But this symbolic focus on male elites can veil the experiences of hundreds of thousands of Armenian women who were left to cope as their husbands, fathers, and brothers were arrested or forcibly conscripted into the Turkish army’s brutal labour battalions. Alone, they prepared their families for the waves of deportations which the Ottoman rulers ordered over the summer of 1915.

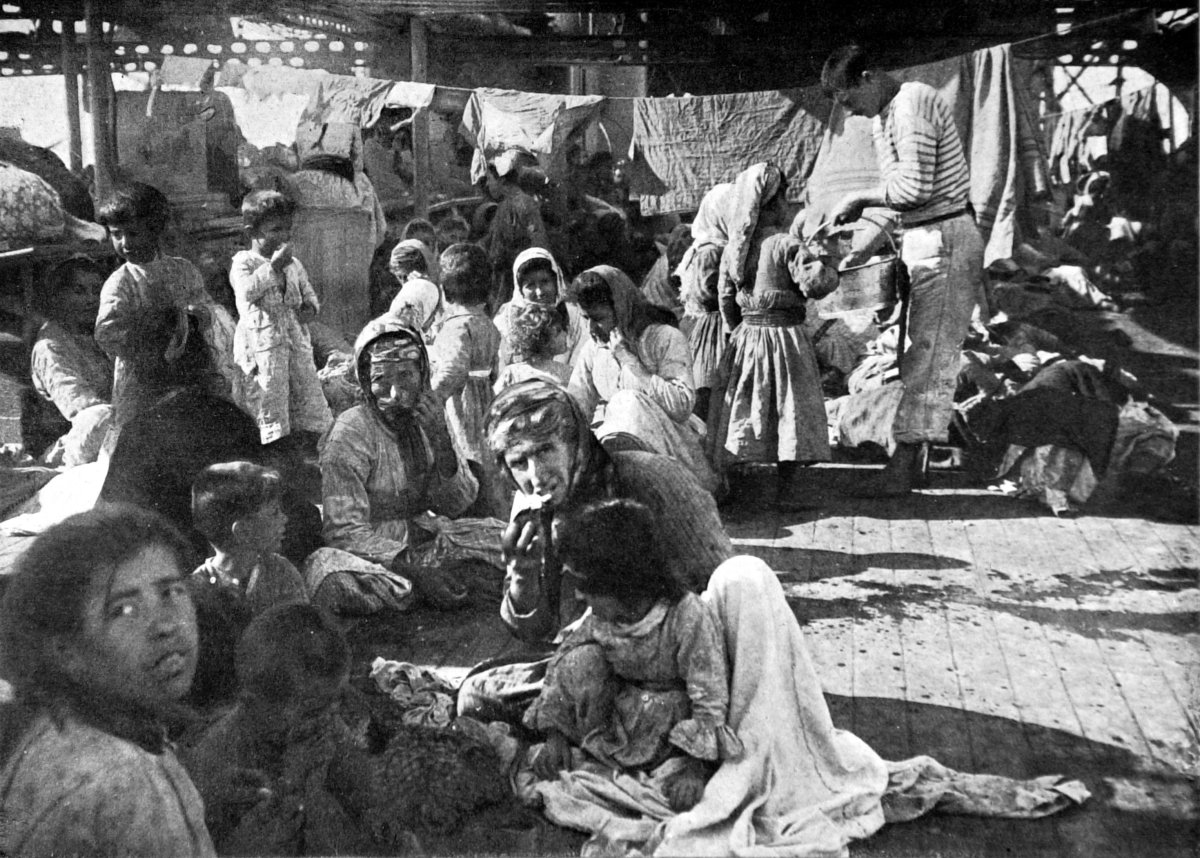

Nearly a million women, children, and elderly were forced to walk across mountainous terrain toward the Syrian desert. They endured extreme heat, exhaustion, hunger, and thirst. Along the way, the caravans were frequently attacked by their own guards and bands of locals, who looted, killed, and raped with impunity. They also abducted children and younger women, keeping them as servants, wives, and sex slaves.

Less brutal locals took in Armenians who had been left behind to die, or struck bargains to marry desirable Armenian women and in return save their families from deportation. In this way, tens of thousands of Armenian women became effectively captives in Turkish, Kurdish, and Arab houses. They were forcibly converted to Islam, had their names changed, and endured protracted sexual violence.

After World War I many managed to escape, joining the remnants of the Armenian community in Aleppo and in other cities around the Middle East. But escape was difficult and dangerous: some women didn’t escape captivity for years.

But the story does not—and should not—end there. Women who escaped often experienced discrimination within the surviving Armenian community: in a deeply patriarchal culture, the forcible conversion, marriage, and rape they endured were deeply taboo.

Of course, some Armenians welcomed their wives, daughters, and sisters with open arms, and some young men—casting themselves in the role of “saviour”—declared that they would happily marry former captives. But others in the community viewed these women as ‘broken’ or “blemished,” no longer suitable to become Armenian mothers and participate in national rebirth.

New taboos emerged, and a former captive’s story sometimes determined the support she received. Women who bore physical scars from their time in captivity—visible or perceptible reminders of sexual violence—were often shunned. Women so traumatised that they were now “mentally disturbed,” in the language of the time, often ended up in asylums.

Women who escaped with children fathered by their captors, or who arrived pregnant, faced the deepest taboo. Very often, these children ended up being given away for adoption, or were returned to their fathers. In other words, women with the most difficult stories were often marginalized in the aftermath.

Survivors of more recent cases of what is now called conflict-related sexual violence—CRSV—face similar challenges as well.

For example, after the Islamic State took thousands of Yezidi women into genocidal captivity in Iraq in 2014, their sexual enslavement was widely reported. Those who escaped were formally reaccepted by the surviving Yezidi community, but new taboos and “hierarchies of suffering” affected the support they received: Those captive for only a short time or who were not raped, surviving as the servants of Arab acquaintances, are frequently denied the government compensation that others receive. Those with children born of rape face the choice of having to abandon or give up their children for adoption, or not return.

In Nigeria, girls who were abducted by the Islamic radical Boko Haram group but managed to escape face distrust from their community and families, and a lack of psychological support for their traumas. Those who returned pregnant—and their children—are frequently rejected by their families, who fear that living Boko Haram members are being thus brought into their midst.

And in the refugee camps in Bangladesh, Rohingya girls who were raped during their expulsion from Myanmar are often forced into child marriages to “save their honor.”

Just as after 1915, some women’s experiences of sexual violence are more “uncomfortable” than others for their communities, and they face much higher challenges as regards basic survival, access to support and compensation, and their human rights.

Humanitarian efforts—and, indeed, awareness efforts—can make all the difference for such victims. So, we might spare a moment for a new exhibition in London—Genocidal Captivity: Retelling the stories of Armenian and Yezidi women.

This important work explores the stories of 10 Armenian women who were all taken in by Karen Jeppe, a Danish relief worker in Aleppo, regardless of their stories. It also tells the stories of 10 Yezidi women who escaped ISIS captivity, who are being helped by charities like Free Yezidi Foundation to access their rights.

These women’s stories of survival deserve to be heard. They deserve compassion, and they deserve equality, and they deserve to be freed not only of their captors but of the captivity of their own side’s benighted prejudices and taboos.